Is this the only way to be and not to be a man?

As world marks Men's Mental Health Month, one person launches scathing inquiries into patriarchy's lasting toxic impact on both masculinity and femininity

Looking back at my childhood, the one thing that amazes me is the consistency of the messaging: at every turn, I was told I was doing it wrong. I was merely a child; however, the world had defined the path ahead of me, and every person was hellbent on preserving that path. The path was one of masculinity and manhood. The path was sacred.

The practice of manhood and manliness has always been seen as a singular expression. This is enforced throughout society at every level.

A teacher at our school once ran after me; our class with him had just ended. It was maybe the eighth grade. He said out of nowhere, "Beta, you mustn’t walk with your hips like that. Walk straight like a man." He then proceeded to roll my shoulders back and told me to walk with my chest instead. This same teacher would later berate me in class for speaking with my hands, again insisting on manliness. I would soon begin speaking to myself in that tone. Whenever I’d pass a mirror, I’d make sure to adjust myself: shoulders back, chest out, hands tucked away.

As a young boy, I found connecting with women easier. My sister, her friends, or just the girls in our social circle—all of them were easier to talk to, connect with, and be myself around. I didn’t have to wear armour around them. They didn’t care about how masculine I was presenting, nor did they seem to care about the “path” to perfection. Of course, there was variation here too; some girls did mind me being around, and there were girls who protected the image of masculinity more than I ever cared to. But the vast majority didn’t really care.

The end goal was to grow into the perfect image of a man, or as close as humanly possible. There were expectations that came with that image. Some of these were visual, much like what my teacher told me: walking a certain way, talking a certain way. The perfect man should exude confidence with his physicality. The expectations were also emotional: a man holds his emotions close, and his heart even closer.

Growing up, I’d rarely seen a man cry — maybe a few times in movies, and that’s it. It wouldn’t be manly to be expressive in love or sadness. The only manly expression was anger, again reinforced by movies. The last expectation of the perfect man was economic: pick a career with “scope,” do something that earns you well and supports you well too. The perfect man was passionate about being the perfect man; all other passions be damned.

This pressure to fall in line has adverse effects on men’s mental health. Add to this the fact that men are not brought up to be comfortable with their emotions, and it’s like being stuck between a rock and a hard place. The proof of this comes from a simple statistic on suicide mortality.

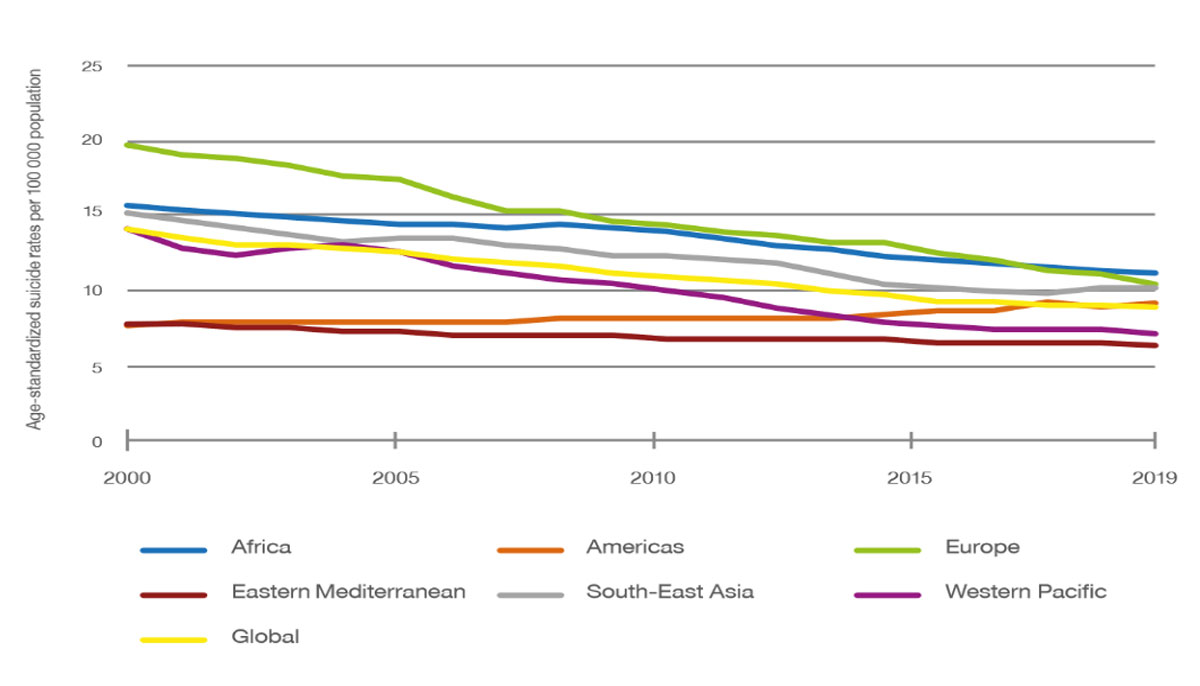

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Global Burden of Disease Study's mortality database ranging from 2000 to 2019, at least 12.6 suicides in males and 5.4 in females were recorded per 100,000 population. The number of men is higher than that of women. This is an international problem, and this is why June has been selected as Men’s Mental Health Month.

I wish I could tell you that this message of masculinity was ever subtle, but the reality was that the goal of being the perfect man was very overt. A distant cousin, who was universally deemed “settled,” visited our home. Soaking in the air of perfection, he “offered” to give me a to-do list to help sort out my life. I recently found the list, which at the time I had hand-written. Reading it now, I felt those items to be so robotic and so detached from who I was. In fact, I do not recall ever being asked by him, “What do you want to do?” It was simply a list of things to work through.

That list and that conversation taught me one thing, and one thing only: the end goal of being considered a “good man” and what I want to do in life are two different things, and I must sacrifice myself in the pursuit of the goal. It pains me to say it, but until I started my undergraduate degree, I was still pursuing that “perfect” man’s image. I had buried my inner self wholeheartedly because I wanted to please, and because the image of perfection and the promise of perfection were too great in my 18-year-old mind.

It is no surprise, then, that those were my most unhappy years. It was the most liminal time — the shift from school to university— where every decision held so much weight, and where following my passion and heart had to compete with fulfilling practical needs and gaining support. As a child, I had already begun the process of shielding myself and forming my image to align with the perfect man. In my late teens, the struggle to shield and mould myself became more difficult because the decisions I faced felt so permanent and life-altering.

I felt I couldn’t fight for myself because I’d let everyone down, and I know that reads more like a confidence issue, but it was because I inherited the feeling that “perfection” was the only ideal and outcome. There was no one to confide in about this because, again, expressing emotion or “feeling the feels” wasn’t really encouraged; after all, a man just “sucks it up and moves on.” Deviating from it would only lead to disappointment. These were all ridiculously heavy things to think through, especially at 18.

The pull between a certain life and what I wanted to do was incredibly difficult to navigate growing up. Life, up until then, had not given me any coping mechanisms. I knew the people around me loved me, but why couldn’t I talk to them about this? Why did I feel so much pressure to stand up for myself? Why did I channel this frustration at the world against myself? Why didn’t I believe in myself, and why was I so quick to assume the world was right instead of understanding myself?

There was no place for me to vent these feelings. There were no safe spaces to express them. Mental health wasn’t a phrase used or even recognized at that time, especially in a desi context. Even for myself, I didn’t have the language I have today about mental health and anxiety. Without that language, I couldn’t even advocate for myself. All of the answers to those questions can be attributed to this incessant desire to create perfect specimens of masculinity.

Patriarchy has defined a cookie-cutter version of a man, and the process of falling into shape is painful. Questioning yourself and succumbing to that pressure is surprisingly easy. Why? Because this system of perfection and masculinity does not give boys and men the tools they need to understand their emotions.

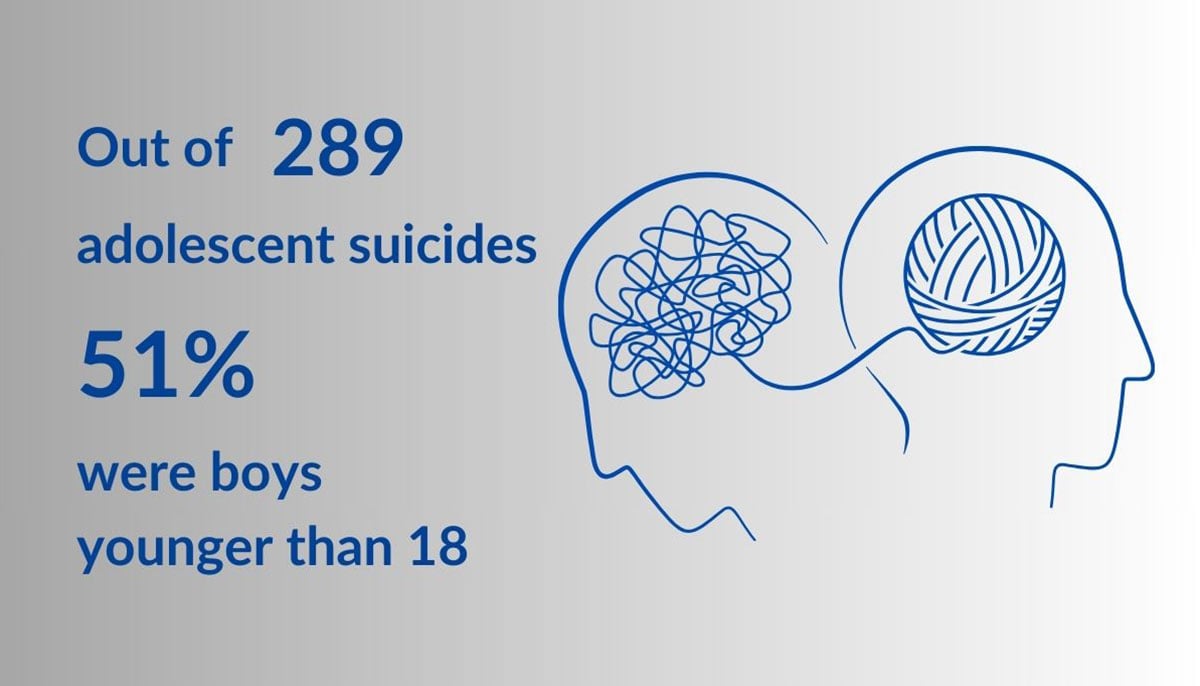

According to the WHO, in 2019, 78% of reported suicide deaths were men. In a 2023 study by the Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, out of 289 adolescent suicides, 51% were boys younger than 18. I was very close to being a statistic like this, but for many reasons, I didn’t go through with it. Seeing these numbers and knowing how high they are brings me terrible sadness. All of this pain and suffering was, and is, so easily avoidable; all it takes is a little love and compassion.

When I started therapy many years after my own attempts, I wanted to find someone to blame. I was so angry that the world around me had brought me so much sadness and self-hatred. But my therapist asked me one simple question: “Do you think any of it was on purpose?” It wasn’t. None of it was on purpose. No one knew better, and change was never really welcome.

With each generation, awareness has grown. The feminist movement has shown us how patriarchy affects all of us and how we must do better for ourselves and for those who will come after us. A 2016 study by the Aurat Foundation found that perceptions of masculinity have changed in Pakistan. It also showed how urban centers are where more restrictive forms of masculinity take hold, but now in rural Pakistan, tides seem to be changing, slowly but surely.

The system of patriarchy hurts us, and it is time that we take its power away. Masculinity and femininity exist in balance in all of us; we cannot shun one over the other. After all, imbalance only breeds further instability.

Arslan Athar is a writer based out of Lahore, Pakistan. He was a 2021 South Asia Speaks fellow, working on his novel with mentor Fatima Bhutto. Arslan's fiction and non-fiction work has been published in numerous national and international publications. He posts on X @ArslanArsuArsi

Header and thumbnail image via Canva