Fight against terror: Where did we go wrong?

Fight against terror’ is too serious an issue to be politicised and used for point scoring

June 27, 2024

Pakistan has come a long way in its fight against terrorism and extremism, which has resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of people, including security personnel, policemen, and top political leaders such as former prime minister Benazir Bhutto and Awami National Party (ANP) leader Bashir Ahmad Bilour, as well as common citizens.

These attacks have varied dynamics across different areas, such as ex-Federally Administered Tribal Area (FATA), Balochistan, and Karachi. Many cities, including the country's largest, have become hotbeds for global and local terror networks.

What is required is a fair and objective analysis of how and why terrorism escalated so severely after 1979 and again post-9/11 during two different wars with distinct objectives. In this fight against terrorism, we have experienced both successes and failures, as often happens in such scenarios. The question is: What is the way forward, and are we heading in the right direction?

Pakistan's security forces certainly have a success story regarding cleanup operations in North and South Waziristan, Malakand, Dera Ismail Khan, and Swat, which at one time almost fell to terror networks like Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and al Qaeda.

Similarly, the Karachi operation post-2014 was significantly different from the previous operations in 1992, 1994, and 1998, which had more political motives rather than a focus on countering terrorism. Before 2014, Karachi was among the most unsafe cities in the country.

Balochistan also required a different approach, particularly after the killing of veteran nationalist leader and former governor Nawab Akbar Bugti. Pakistan’s two Afghan policies under military dictators General Zia-ul-Haq and General Pervez Musharraf made Pakistan more insecure than secure.

The biggest dilemma over the past three or four decades has been the lack of political will, consensus, and a unified approach, especially when it comes to countering extremism. As a result, we have witnessed incidents like those in Swat and, in the past, incidents such as those in Sialkot or the Mashal Khan case in Mardan.

However, where we have miserably failed is in post-operation reforms, the lack of a strong criminal justice system, and the protection of witnesses in such cases. Even laws like the Anti-Terrorism Act have been politicised, targeting political leaders and workers.

Neither the jails were reformed, nor was the police, resulting in many terrorists being granted bail or acquittal. The lack of political will and differing opinions on handling extremism have also caused serious setbacks.

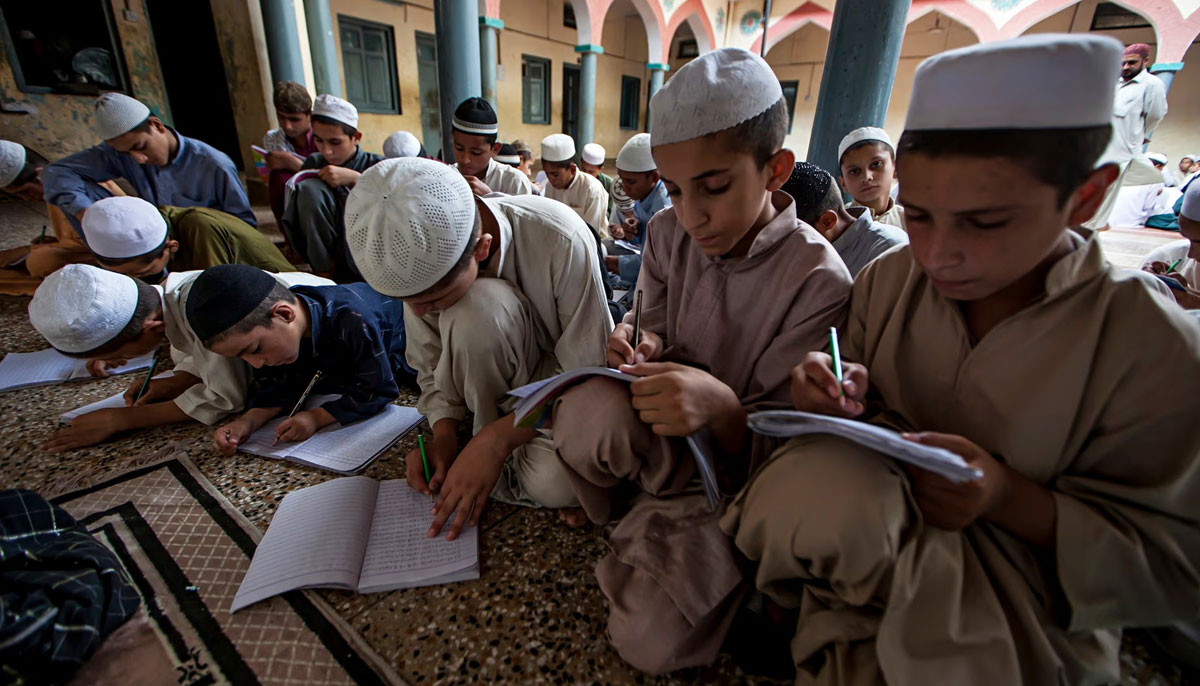

For years, we have focused on ‘reforming’ madrassas but never tried to improve our education system and government schools. When millions of children can’t attend school, they become more vulnerable to extremist networks. Reports indicate that even juvenile prisoners often fall into the hands of terror groups and become more vulnerable. All these issues were part of the National Action Plan (NAP) of 2014, which has seen zero success.

So, the events that transpired in the last few days laid bare the government's naive approach, which has created confusion, followed by powerful meetings of the Apex Committee of NAP to review the ongoing fight against terrorism and develop future strategies.

The operation was given a new name, 'Azm-e-Istekham,' leading to confusion, especially due to how it was portrayed by ministers amid backlash from the main opposition party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), which has been in power in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) since 2013, and even from parties like Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F) and Awami National Party (ANP), both of which have been the worst victims of terrorism.

The fight against terrorism is too serious an issue to be politicised as it was due to the government's mishandling. This led to a clarification being issued as the matter began turning into an ethnic issue. The opposition also failed to present alternative solutions.

Opposing the operation is one thing, but the question remains: what is the solution to terrorism and extremism? The opposition parties have also failed to provide suggestions. PTI has been in power in KP since 2013, JUI-F and JI were in power from 2002 to 2008, and Pakistan People's Party (PPP) and ANP were in power from 2008 to 2013. What have they done in this regard?

Sources indicate that powerful quarters were unhappy with how the Apex Committee’s decisions were misinterpreted. A longstanding demand to include a leader of the opposition in the 'apex' at the centre and in the provincial committees should have been met when the committees were formed after the 2014 massacre of nearly 150 children and teachers at Peshawar’s Army Public School.

You can’t be allowed to take political mileage out of a serious issue like the fight against terrorism, as it has far-reaching consequences and requires national consensus. This is despite the ‘soft corner’ or misleading approach of certain groups and parties, which have inadvertently benefited terror and outlawed groups.

Unfortunately, the message did not resonate well, as only days before the Apex Committee meeting, all political parties sent a very positive message of unity in their meeting with the high-powered Chinese delegation. This was to reassure the strong ties between the two nations and demonstrate complete consensus on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and other matters of cooperation.

What the government and the Apex Committee need to do urgently, if we truly seek ‘political consensus’ in the crucial ‘War against Terror,’ is to arrange a complete and comprehensive briefing in Parliament. I believe this should not be ‘in-camera,’ as people have a right to know the successes achieved in this fight since 9/11 in general, and particularly post-2014.

Secondly, unless there are issues of a ‘sensitive nature,’ the minutes and decisions of the Apex Committee should be made public now and in the future.

Thirdly, the leader of the opposition at the centre and in the provincial apex committees should also be included in the apex. Fourthly, the central apex committee should meet every quarter and the provincial apex committees monthly to review performance.

Parliament, on its own, can have an 'All Parties National Committee' to oversee the implementation of the NAP quarterly. Lastly, National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA) Pakistan should play a more proactive role.

Pakistan’s dilemma for a long time has been its poor handling of the fight against global and local terror networks, as well as sectarian and ethnic strife.

The way terror networks formed their sleeper cells since the early 90s is baffling. I still remember the way two American diplomats, allegedly undercover agents, were killed on the main Sharea Faisal in 1994, followed by the arrest of Ramzi Yusuf, a key figure in the first attempt on the World Trade Towers in New York. He was arrested in a joint operation by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Later, in another incident, Aimal Kansi was arrested from a guest house in Islamabad again in a joint operation, as he was wanted for the killing of two Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) men in the US. This in itself triggered a debate in the press regarding the role of the FBI or CIA in Pakistan.

All this happened much before 9/11, as Pakistan became a hotbed for these terror networks. In 1994-95, then prime minister Benazir Bhutto took the bold step of handing over hundreds of suspected militants of Akhwan-ul-Muslameen to Egypt as they were Egyptian nationals, leading to the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad being blown up in a suicide attack.

A month before 9/11, Pakistan banned all sectarian outfits in August and confiscated their literature and assets, as well as seizing their bank accounts. However, the ban hardly made any impact as these outfits continued their operations under different names.

Our handling of the post-9/11 situation also remains counter-productive, as we failed to secure our western border, resulting in a massive influx of some of the world's most wanted militants linked to terror networks like al Qaeda.

Most of their leaders were arrested in Pakistan, but not before they wreaked havoc through attacks on our security forces, liberal and secular political leadership, as well as ordinary citizens. The drone attacks also resulted in the killing of innocents, fueling massive anger among the people of former FATA areas. Though Pakistan officially condemned drone attacks, the fact remains that the CIA and FBI were fully involved.

Soon after a US-led coalition attack on Afghanistan, Pakistan's settled and unsettled areas in KP and former FATA fell under the control of these groups. Areas like North Waziristan, South Waziristan, Malakand, Swat, Dera Ismail Khan, and related regions came under the control of non-state actors.

Balochistan exhibits diverse political dynamics, characterised by terrorism associated with sectarian factions, sympathisers of Taliban and al Qaeda, and movements advocating Baloch nationalism and separatism. Similarly, Karachi has long been gripped by ethnic and sectarian strife, once a hotbed of local and global terror networks.

The political and nationalist parties should get involved and play a more proactive role in addressing the cases of missing persons and extrajudicial killings.

Moreover, the biggest miscarriage so far has been the lack of post-operation reforms in areas like former FATA and Swat, as promised by successive governments. However, the Police Reforms of 2002, in their original form, could be a step in the right direction.

The dilemma lies in the fact that political leadership and successive provincial governments want to keep the police under their control, making it difficult for bodies like the Apex Committee to perform effectively. Changing this policy and perception is one of the most serious challenges in handling terrorism.

The fight against terror is too serious an issue to be politicised and used for point scoring.

The writer is a columnist and analyst for Geo, Jang and The News. He posts on X @MazharABbasGEO

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.