The law must prevail

Part of the problem is that statutes against false allegations are not the only ones that are expressly flouted

June 27, 2024

The searing images of the Madyan barbarity continue to haunt us. These are at par with the Sialkot tragedy where a Sri Lankan was beaten to death and burnt. Had the state made an example of those involved, maybe Madyan would not have happened.

There have been other incidents, like the one in Sargodha recently, in which a citizen was assaulted and killed. I am not saying he was a Christian because religious identity in many such cases is unimportant. More Muslims, according to some reports, have been charged with blasphemy than minorities. Many are in jail, but some have been killed in mob violence.

A small news item in one of the papers today caught my attention. The police arrested a group of people in Okara who were getting ready to commit a blasphemous act and pin the blame on their opponents. This is not an isolated case. There is enough evidence that charges of blasphemy are often made to settle a personal score.

There are laws to check this, but they seldom work. Part of the problem is that statutes against false allegations are not the only ones that are expressly flouted. Many other laws exist on paper but are openly violated and often by the state itself. This creates a free-for-all atmosphere where breach of law becomes acceptable.

The right to a fair trial for example is the basis of a civilised society and state. But it is neither respected by the police nor in many cases by enraged citizens.

Karachi is a classic example of this vigilante lawlessness. Criminals in the city are on the rampage and daily kill people in street robberies. The citizens have responded by taking justice into their own hands and instead of handing over alleged robbers to the police, they are lynching them on a daily basis. Alleged criminals because the possibility of the wrong person becoming a victim can never be ruled out.

The police force, particularly in Punjab, has also become judge, jury and executioner. It decided years ago to eliminate what it termed as serious criminals on its own. This started the practice of fake police encounters. Only now, the pace has increased. People being killed in these encounters are multiplying by the day.

Nobody in the police is even bothering to come up with an inventive or decent cover story. The narrative is the same now, across the province. It goes something like this: the man in custody was being taken to the crime scene when his accomplices killed him in trying to rescue him. Miraculously, the police transporting the accused did not get hurt and the accomplices of the accused (always) managed to escape.

The justifications for this lawlessness by the police and people are many. The citizens in Karachi have given up on the police. Subjected to years of violent crime, they are angry and in no mood to trust the system. This pent-up rage transforms into mob violence killing whoever is suspected.

Part of the problem is that there is no fear of retribution for this vigilantism. No danger of being held to account by the state. In fact, the mood is one of jubilation; of having done a good deed to rid the world of filthy vermin. At least I am not aware of anyone ever arrested by the police for this vigilantism. If ever such an attempt were to be made, the public would be outraged. How can somebody be charged for a noble act?

Police vigilantism in Punjab started in the late eighties under Nawaz Sharif and got momentum during various stints of Shehbaz Sharif as chief minister. The justification in the police mind was the same: an unworkable slow and ponderous judicial system. A system that has so many loopholes that a criminal is almost never punished. The only way to create a deterrence, so the police believe, is to become judge and executioner themselves.

There are other examples of the law being ignored or flouted by the state. The issue of missing persons is an example of the law being evaded to justify what is perceived to be the larger national interest. The storyline is again similar to the police narrative: that the system is too weak to punish the enemies of the state. Again, the target is largely the judiciary but the police also are not seen so favourably. They are regarded as corrupt, weak and spineless – and thus incapable of defending the national interest. Both have to be bypassed.

The sad, almost tragic, part in all these examples – and one could give more – is the acquiescence of the people to whatever is going on. Missing persons may be an exception because there are other layers linked to this issue. There are protests against it and sit-ins that draw attention. Lately the courts, in particular the Islamabad High Court, have started to take notice and attempted to hold state agencies to account. This may act as a deterrence.

There is no such notice taken of citizen vigilantism. It is not only ignored but is silently, if not publicly, applauded. Religion-based vigilantism evokes a quick and visible reaction. But, it would be instructive to find out what happened to those arrested earlier for such crimes. A current case in point would be the fate of the 23 arrested so far in Madyan. It could be a case study to see what kind of prosecution is done and how the courts react.

In case of police encounters, when was the last time that people in general came out on the street to protest these extrajudicial killings? Now and then some families may protest but it almost seems as if the public has largely internalised the police narrative. There is a tacit acceptance that the system does not work and when some child rapist or serial killer is eliminated in an encounter, no one bothers.

The problem is that the decision to eliminate is not taken by a judge after a fair trial under the laws of the state. We would all like barbaric criminals to be punished – but after due process of law. If today the law is ignored in the case of dangerous criminals, tomorrow it will be for you and me. Becoming judge, jury and executioner gives a licence to act with impunity and without fear of accountability. This is a terrible power, whether in the hands of the police or other elements of the state.

It is thus that rule of law is a fundamental attribute of a civilised state. The Nazis tried in Nuremberg were mass murderers but they were not lined up against a wall and shot. They got a trial – however pre-ordained the verdict may have been. In a country of laws, barbaric criminals are protected to ensure due process, not executed with impunity.

We have to decide once and for all whether we are a country of laws or a chaotic state where anything goes. If our laws or the system has weaknesses we have to fix that rather than give up and descend into an anarchy of the powerful. Rule of law must prevail over brute force.

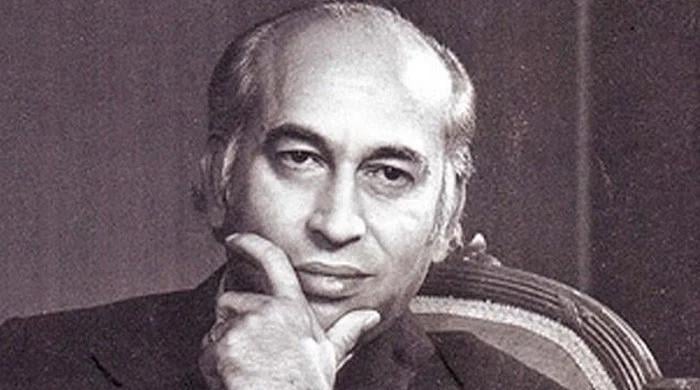

The writer served as the federal minister of education in the PTI’s federal government. He can be reached at: [email protected]

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

Originally published in The News