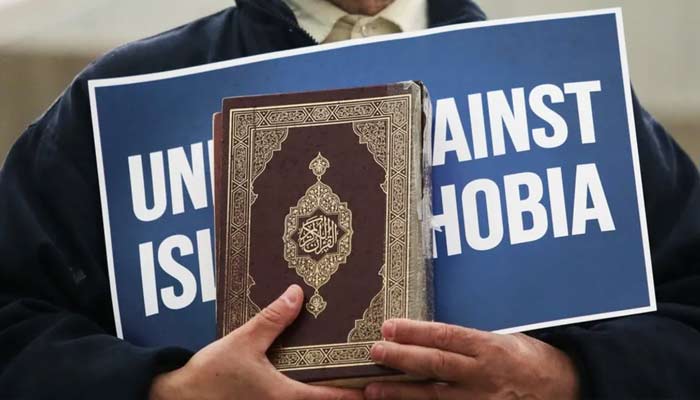

Muslims face growing Islamophobia in UK Elections 2024

Most commonly targeted group in religious hate crime offences in England and Wales were Muslims

July 01, 2024

As in 2019, Islamophobia has been a mark of this year’s general election campaign, most overtly in relation to the Reform party’s pro-British Values, anti-immigration platform, but also because both Reform and the Conservative party have allowed candidates to represent them who have known anti-Muslim sentiments.

Farage himself has returned to the spotlight, running in the Clacton constituency where the only UKIP MP has ever been elected and where immigration is a top issue for constituents. He had initially stated that he would not run because he did not anticipate the prime minister calling an early election and thus did not have the necessary time to campaign, but he u-turned on this position in early June. He announced that he would like to lead a “political revolt” against the “status quo.”

One candidate standing for Reform, Dionne Moore Cocozza, previously stood for the Brexit Party in 2019 and, during that campaign, she had said on social media that Muslims “abuse” the label “fascist” in order to “cover up” their “resentment” of the UK and that they want to change the UK’s laws to conform with the “oppressive” Shari’ah. Sky News has noted how, in this election, she is standing for Reform under the altered name Dionne Moore in Glasgow West.

But such narratives cannot be considered fringe within the party. Farage gave his first interview in this election campaign to Sky News as the honourary president of Reform, saying that “we have a growing number of young people in this country who do not subscribe to British values, in fact, loathe much of what we stand for.” When prompted by interviewer Trevor Philips as to who he was referring to, he confirmed that he meant Muslims.

In this interview, and another given to Good Morning Britain, Farage has relied on a survey conducted by JL Partners as the basis of his concerns about the Muslim community. This survey questions to the general public, and then specifically adult Muslims in the UK, on topics like introducing Shari’ah law in the UK, Jewish influence in the country, important issues ahead of the elections and on the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

Farage quoted the survey as showing that 23% of 18–24-year-old young British Muslims think that “jihad is a good thing,” saying that this is “not a British value.” To be precise, the survey found that 11% of the 171 18-24-year-old Muslims (of the 1,000 Muslim adults in the UK surveyed) believed that jihad was “very positive” and 12% responded that it was “quite positive.”

But Farage fails to account for two things. Firstly, jihad has become a catch-all term in the West and is often used to mean a “holy war” or violence used by Muslims, which is tied to stereotypes of the group as violent and as terrorists. But neither Farage nor the survey define jihad, and it is a far more complex concept than is often acknowledged, encompassing struggles against oppression and injustice or an internal struggle against immorality and evil.

Are these things that Farage would oppose on principle? Secondly, even if some of the Muslims responding to the survey perceived jihad purely as armed struggle, the overall responses show that more Muslims believed that jihad is “neither positive nor negative” (29%), which perhaps reflects the nuance of the term, and even “very negative” (23%) than those in the specific age bracket quoted by Farage who perceived it as very or quite positive.

Farage’s interviews reveal a primary narrative of Reform UK: that mass migration has allowed people into the UK who are opposed to ‘British values.’ It is in the name of protecting British values and improving access to public services and integration that they support net-zero immigration. To exemplify integration failures, the town of Oldham is regularly invoked by Farage and his supporters as having streets where “virtually no one speakers English.” Farage has consequently suggested that this “should be the immigration election,” with Reform UK touting itself as the only party prepared to address the immigration issue. He has repeatedly used dehumanising terms like “population explosion” and “invasion” to describe immigration to the UK.

James O’Brien dismantled one Farage supporter on an LBC call-in for his regurgitation of the Reform UK narrative that Farage will protect British values against Muslims. When O’Brien pressed the supporter for an example of people coming here “wanting to change our rules,” the supporter named Mayor Sadiq Khan (who is of course British!) as wanting to establish Shari’ah law in London because of his Islamic faith, quoting a social media post.

The post is originally from 2020 and attributes a quote to Khan to the effect that he was “trialling shakira law in three of London’s boroughs,” but, unsurprisingly, it was shown to be false by a Reuters fact-check (note the misspelling of Shari’ah, too). The supporter alleged that because Khan is a Muslim, “of course he wants Shari’ah law.” While the supporter conceded that he was wrong about Khan, which O’Brien rightly shows to thus be a misinformed basis for his support for Farage, he was unwavering in his support for Farage.

Like with the concept of jihad, these anti-Muslim narratives fail to engage with what Shari’ah actually is and Muslims are characterised as Islamists in wanting to establish Islamic law and an Islamic system of governance.

The people who espouse such narratives are not only unaware of the differing shades of opinion within the Muslim community itself, but also the areas of overlap between so-called ‘British values’ and Islamic values, such as democracy (consultation in Islam), respect and social justice. It is simply a redressing of the view that “good” values and human rights originate in the West and are alien to Islam.

But overt Islamophobia has been prevalent in the Conservative Party too, with Sadiq Khan again being the subject of suspicion. Lee Anderson said in February, when a Conservative MP, that “Islamists” have got “control of Khan,” Keir Starmer and London. After refusing to apologise, Anderson was stripped of the whip and he is now running as a Reform candidate.

But the refusal of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to explicitly refer to this as Islamophobia, only that Anderson’s comments were “wrong and unacceptable,” reflects an implicit Islamophobia, insofar as politicians regularly express contempt, suspicion and prejudice towards British Muslims openly, but it is not recognised as a very specific form of racialised, anti-Muslim hate.

Yet, the most commonly targeted group in religious hate crime offences in England and Wales were Muslims, at 44% of all recorded offences of this nature in the year ending March 2023.

While Anderson was expelled from the Conservatives, Suella Braverman is running again for the party, despite having made sweeping remarks about British Pakistani men in April 2023 in the context of child grooming. She said that there was a “predominance of certain ethnic groups, and I say British Pakistani males, who hold cultural values totally at odds with British values to see women in a demeaned and illegitimate way.” This reflects the racialised nature of Islamophobia, as anti-Muslim sentiment often overlaps with racism against Brits of South Asian ethnicity, especially British Pakistanis.

This is also apparent from the demographics of towns invoked by Reform as examples of failed integration. For example, 25% of residents in Oldham identify as ethnically Asian or British Asian and the second most common country of birth for residents after England was Pakistan. Some Oldham residents have criticised Farage’s use of Oldham’s name and his accompanying divisive language.

It is not the purpose of this article to claim that there are no problems within the UK’s Muslim community, nor that Islamophobia is the only form of discrimination that is prevalent and needs to be challenged. Opposing Islamophobia does not negate legitimate criticism, and to be truly committed to eradicating injustice requires condemnation of all forms of discrimination. But the prevalence of Islamophobia, as a racialised suspicion of and prejudice against Muslims, within yet another election campaign shows two key things.

Firstly, that it is not always considered a unique type of racialised prejudice or even discriminatory at all, and thus not grounds enough for removal of a person from a political party or public office. Secondly, that enough of the general public are sympathetic to Islamophobic narratives to motivate populist, right-leaning politicians to use them as the basis for their electoral platforms.

The author is a post-doctoral researcher and writer with interests relating to Pakistan, Islamophobia and Pakistani diasporas in the UK.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.