Bandwidth bandits: Internet regulation riddle strikes VPNs in Pakistan

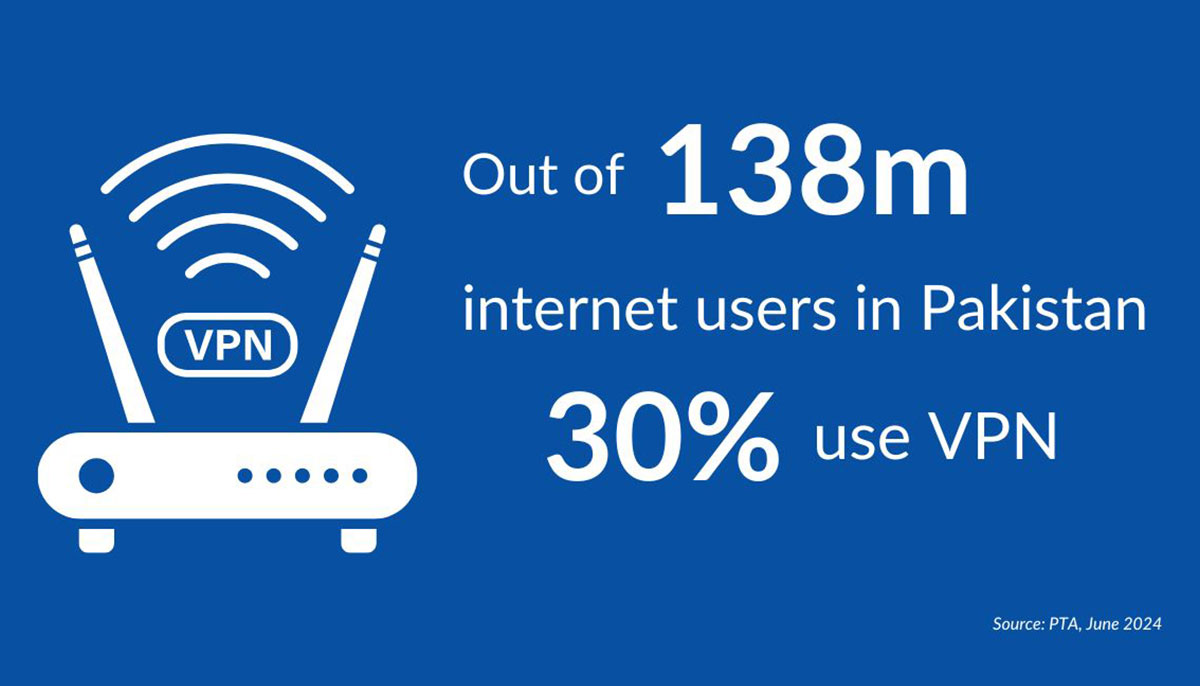

PTA says 30% internet users in Pakistan use VPN with usage witnessing a 131% surge after govt's ban on X on February 17

"A large number of people are using VPNs to bypass cache data and accessing live internet, which has put pressure on the live internet leading to a slow speed.”

This is what Minister for Information Technology and Telecommunication Shaza Fatima Khawaja said in a press conference on August 18 after a long silence on why the internet has been slow for the past few weeks in the country.

The government has been trying to bring Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) under its regulation window for more than a decade, with the first known notice issued by the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) in 2011 directing Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to give details of VPN users in the country to the regulator which will allow it to ban any service that is not registered with the PTA. And the trend has continued ever since with the government forcing businesses and individual freelancers to register their VPNs with the authorities to continue to use them, a practice that the regulators refer to as “whitelisting”.

Notices in 2014 and 2022 were issued again asking businesses to register VPNs and respective IP addresses to continue to operate in the country, which the government says it is empowered to do under the Monitoring and Reconciliation of Telephony Traffic Regulation 2010 (MRITT). This Act focuses on monitoring and controlling international telephony traffic, particularly to prevent illegal VoIP services and ensure revenue collection from international calls. However, the principles of monitoring and surveillance established under the MRITT contribute to the regulatory environment in which VPNs are also controlled.

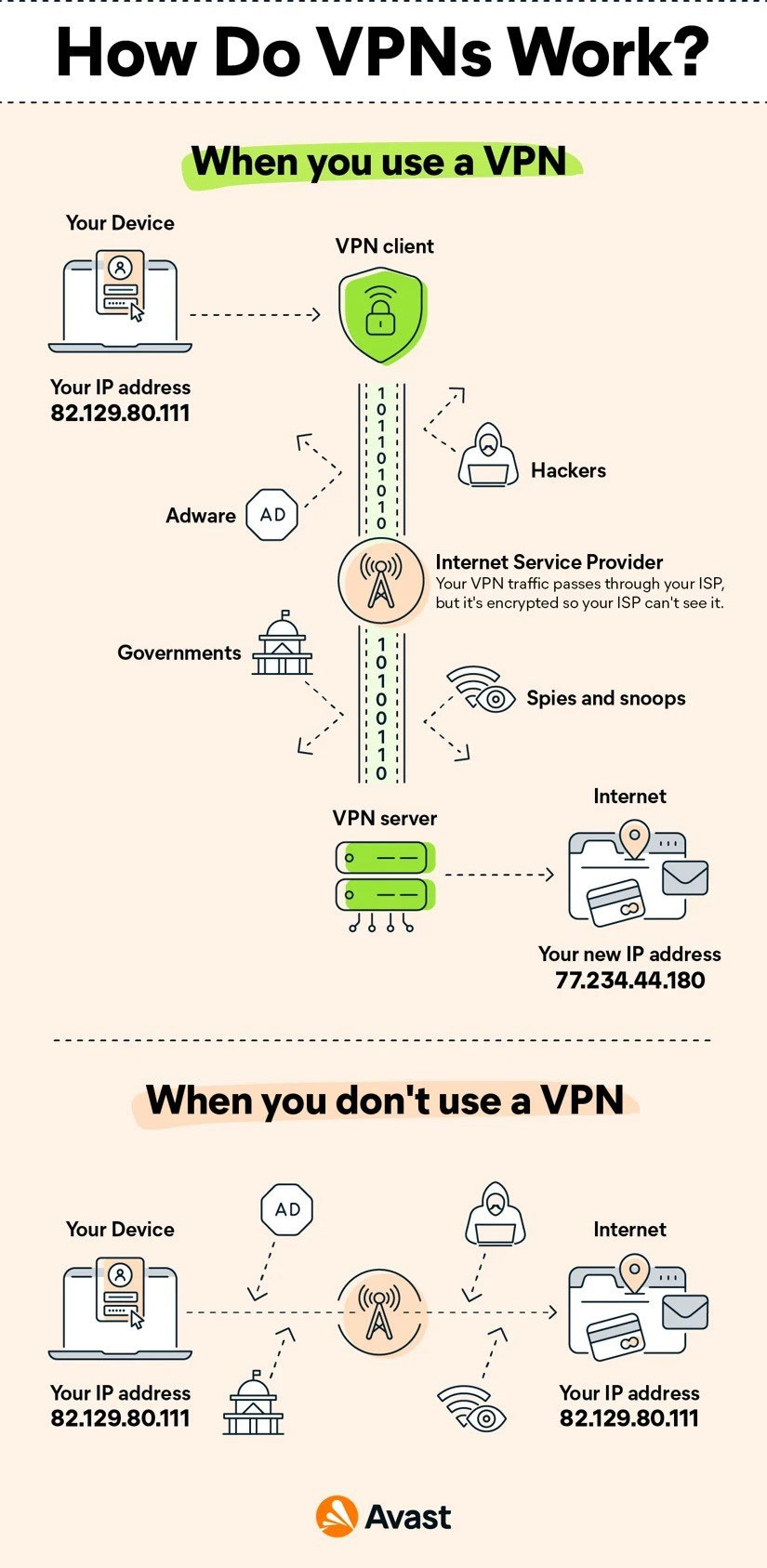

The implications of the requirement to register a tool like VPN are severe and it would be naive to assume that the government is unaware of the impact. People use them to protect their online privacy and security by encrypting internet traffic, thereby safeguarding against surveillance and cyber threats. VPNs also enable users to bypass censorship and access restricted information, promoting the right to information and freedom of expression. Additionally, they are vital tools for maintaining digital autonomy in environments where internet freedom is under threat.

The demands to register VPNs with the government hinder all of these rights: governments can surveil citizens’ online activities, infringing on their right to privacy; it can have a chilling effect on freedom of expression; and the ability to bypass censorship would also be curtailed.

The PTA chairman, in a Standing Committee meeting on August 2, said that the government is working on a plan to regulate VPNs, after which only whitelisted proxy networks will be allowed to function in the country. The said plan has not only been lacking transparency, the comment also indicates that the government and its officials do not fully understand how the technology works.

Successful regulation of VPNs is a challenge in current times as there are always options available that enable users to find alternatives. With the availability of open-source technology which is built on publicly available code, VPNs can be modified, forked, and redistributed by anyone. This decentralisation makes it difficult for governments to control the entire ecosystem, as new versions or variations of the software can emerge quickly in response to regulatory efforts. This technology is often supported by global communities committed to privacy and freedom of expression — a collective effort makes it harder for governments to regulate specific entities or companies, as there may not be a single point of control or responsibility.

Pakistan has a robust history of censorship which has led to the popularity of VPNs amongst the masses as these circumvention techniques have become the only way for them to access the internet. The PTA says that 30% — 41.4 million out of 138 million, as of June 2024 — of the internet users in Pakistan use VPN, a usage that witnessed a 131% surge just two days after the government banned access to X, formerly Twitter, on February 17, as reported by Top10VPN. This serves as a clear indication to policymakers that censorship efforts tend to drive individuals towards the very circumvention technologies that the government is currently attempting to restrict.

These are different times from when the government blocked YouTube a decade ago, for instance, when users not only turned to alternatives such as DailyMotion and Vimeo for video content, but also actively made attempts to access the controversial video that originally prompted the years-long ban. Repeatedly, it has been demonstrated that the internet cannot be effectively or fully censored due to the persistent replication of content and the availability of technology that facilitates access.

However, the country’s economy suffered disproportionately during the ban, with lasting effects that have not yet been fully mitigated. The current wave of censorship exacerbates this damage, posing significant risks to the present and future of the digital economy and the livelihoods dependent on it.

For instance, Fiverr, a platform that connects freelancers with global projects, has suspended the accounts of Pakistani freelancers due to the increasingly unstable internet conditions in the country, particularly unreliable connection speeds. This has resulted in many individuals losing their primary source of income. The Pakistan Software House Association for IT and IETS (P@SHA) estimates that this instability could cost Pakistan’s economy over $300 million in losses. For a nation already grappling with severe financial challenges and relying heavily on debt, such economic setbacks should not be compounded by avoidable disasters.

VPNs are widely recognised around the world as crucial for ensuring privacy, security, and unrestricted access to information. However, their use is regulated to varying extents, with some countries imposing strict controls or outright bans on some services, particularly in regions with restrictive internet governance. The global context for VPNs is constantly shifting, as governments intensify their scrutiny and concerns about digital rights and privacy grow.

Authoritarian governments like North Korea, Russia among others, around the world have restricted the usage of VPNs in attempts to control the spread of information, exercise rights to privacy and freedom of expression and control political opposition. According to Surfshark, almost 45% of the global internet users live in countries that control the use of VPNs in some ways — that’s 2.4 billion people worldwide, with Pakistan’s 138 million broadband subscribers amongst them. Despite these controls, people reported to have still used VPNs for various reasons, including work.

Pakistan’s internet regulation has been going through its formative years endlessly for the past two decades, with multiple governments that assumed power trying various approaches to control speech on and access to the internet. It has not made positive strides so far, but has broken the network multiple times.

More recently, the government confirmed in Islamabad High Court that it has a Lawful Interception Monitoring System (LIMS) in place that enables the government to surveil at least 4 million telecom subscribers’ telecom activities in real-time, along with setting up a “Firewall” to control the flow of internet traffic. Details of these measures are unknown owing to the secrecy these tools are implemented.

Digital rights advocates have frequently highlighted the impact of Orwellian technology on Pakistan's networks, yet it’s also crucial to examine how language shapes the narrative around these authoritarian measures. The LIMS is directed to conduct mass surveillance on Pakistani networks which, the authorities say, is in line with the legal framework of the country under various laws, including Investigation of the Fair Trial Act 2013, Pakistan Telecommunication (Re-Organisation) Act 1996, Telegraph Act 1885, and the most recent Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016.

However, something being legal does not mean it is constitutional. Supreme Court precedents — the case of Benazir Bhutto and Ors vs President of Pakistan 1996 — establish that mass surveillance and interception of phone records is unconstitutional and infringe on a person’s right to privacy under Article 14 but also is against their right to life and dignity.

Key legislations legalising surveillance with conditions

The authorities have also been busy implementing a "Firewall" to establish control over the internet in the country. IT Minister Khawaja said in her press conference, "It is the right of the government to [take such measures] given the cyber security attacks that this country has to go through."

But there is an interesting discussion to have about the nomenclature of authoritarian measures like LIMS and Firewall. For example, Cisco defines a firewall as "a network security device that monitors incoming and outgoing network traffic and decides whether to allow or block specific traffic based on a defined set of security rules. Firewalls have been a first line of defence in network security for over 25 years."

The use of a term associated with security to describe a surveillance framework that does the opposite attempts to shift public perception. Meanwhile, the government continues to present these measures as necessary for national security, strategically using security and rights-based language to alter the narrative.

A recently launched online database, Surveillance Watch, revealing the presence of surveillance tools in countries around the world, reports the presence of spyware tech of 15 surveillance entities notorious for involvement in human rights violations globally, on Pakistani networks – including FinFisher which was first found on PTCL networks in 2013, as well as the Israeli NSO Group. Among the list is also Canadian company Sandvine which the PTA acquired its Web Monitoring System (WMS) from in 2018 at $18.5 million — now extended by advanced LIMS.

Over the past decade, successive governments have left the public uncertain about how they will manipulate the internet during their tenure. Will it involve a crackdown on encryption, the introduction of laws that place Pakistan on the global stage of authoritarianism, the imposition of invasive surveillance tools on citizens, or suppression of freedom of expression and press freedom? Perhaps it will be a deliberate effort to stifle all civil liberties simultaneously by introducing these measures at once, making it the most memorable tenure in recent history. For technology users in Pakistan, the situation is perpetually unpredictable.

Recent incidents in Pakistan have caused significant disruptions: individuals are struggling to connect with family members abroad due to network throttling; immigration personnel face difficulties accessing critical systems at airports; remote workers and freelancers are losing job opportunities in an already struggling economy; and the country is projected to incur losses estimated at $300 million.

In its efforts to regulate — rather overregulate — the internet, the government is infringing upon the rights of its citizens, which it is constitutionally obligated to safeguard. What’s unclear is that when the government says it has the right to take certain measures, does it take into account that it has a bigger responsibility to protect the interests and rights of the citizens it is elected to serve? Rights are reserved for the citizens which the governments have the responsibility to protect. Unless the government realises and acknowledges its responsibilities towards its citizens, people will continue to be the ones bearing the brunt of the authoritarian regulatory regime in a democratic country.

The citizens of Pakistan are not unaware of censorship circumvention measures, thanks to the rich history, robust present and bleak future of digital disruptions in the country that demand awareness of the latest technology that enables the usage of the digital spaces. The government has increasingly been spending its resources, efforts and time to overregulate the internet — the latest list of these regulations appears to be long with news of surveillance and censorship tools that the government is implementing on telecom networks in the country, along with painfully slow internet speed hindering people’s participation in online public spaces.

The need is for the government to revisit its priorities as the country grapples with the economic doom, and refocus and readjust its efforts on strategies that not only enable digital participation of citizens, but also invite foreign business partnerships and investments in the country. More importantly, the government needs to start understanding how modern technology works, and acknowledge its potential for the country’s gains over political interests. Until this happens, the prospects for a Digital Pakistan remain grim.

Hija Kamran is a digital rights expert who focuses on policy advocacy around issues of privacy, data protection, freedom of expression, among others. She posts on X @hijakamran

Header and thumbnail photo via Canva

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.