I don't think I've ever met friendlier people in Pakistan, says David Sedaris

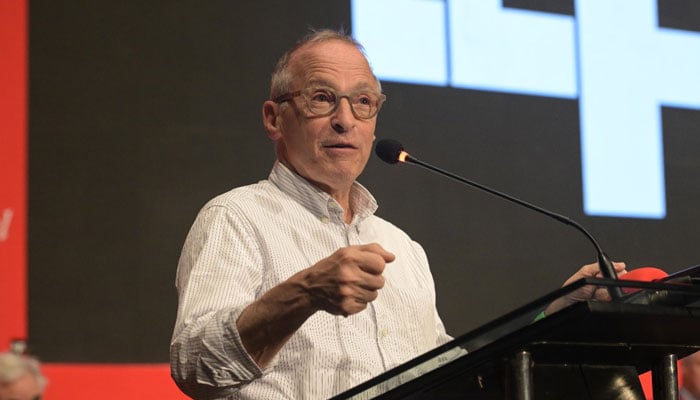

Meet humorist and best-selling author David Sedaris in an exclusive interview with Geo News

August 29, 2024

Critically acclaimed writer David Sedaris was in Pakistan to speak at the 2024 edition of the Lahore Literary Festival (LLF) last February. We caught up with him to discuss his impressions of the country, the often-tortured nature of an artist, and more. Excerpts:

How is Pakistan different from what you expected or imagined?

To tell you the truth, when I told people I was coming to Pakistan, they said you can’t go to Pakistan. They said it’s too dangerous. I’ve been so struck by how kind everyone has been. I can’t tell you how many people stopped me in the street — and they had no idea who I was — to just shake my hand and say: ‘Hello sir, where are you from?’ I don’t think I’ve ever met friendlier people in my life. When I get home, I’m going to tell everybody you have to go to Pakistan. It’s been a wonderful experience; I have really enjoyed it.

That is great to hear, because most people have less-than-stellar things to say.

Maybe they don’t travel enough. I went to the [Lahore] Museum and people stopped me and asked me to take a picture together. Also, the food has been great, a delight.

Is there a chance your Pakistan experience will make it into your next book?

Oh, yes. I’m already writing an essay about my time here.

Any particular highlights from your trip?

It’s nice to go to a place where you don’t speak the language, you can’t read it, and you just have to look around and guess what’s going on. What’s even better is when you’ve got someone who lives here who can explain things to you that they know. Like, I saw a sign that somebody with a tray of birds covered with a net had. I thought that people buy those birds and eat them, and then someone said, ‘No, you pay and then let the birds free.’ Then I saw a picture of mice that was [pasted on the side of a] truck and I thought, oh, you can pay to let the mice free and someone said, no, that’s the exterminator. I’ve had a number of experiences like that which I think would be fun to write about. If you lived in Tanzania, you wouldn’t want to hear what I have to say about Tanzania. But Pakistan? Thumbs up.

What is humour and where does it come from? Are all funny people inherently sad and damaged?

I’m sad and damaged. I can’t speak for everyone. But my sister [comedienne and actress] Amy [Sedaris] is very funny and she’s not sad and damaged. But I am. I just have a hole inside that can never be filled. I need applause and I need laughter to go into that hole, and there’s no amount that will ever fill it up; I need an endless supply or I would curl up and die. I don’t know why — I’m afraid to go to a psychiatrist — and I don’t know that I want to know. I’d be afraid that if I understood that, then I would stop writing or I would stop performing. I just keep on going. Actually, I’m not that sad, I’m just damaged. I think most people who are on stage, they’re trying to get by until they can get somewhere else. But I would rather be on stage looking for [affirmation] than to have gotten it in the first place. I divide the world into two groups: there are people who pay someone to listen to their problems and then there are people who get paid for telling people their problems. I’d rather be someone who gets paid for telling people my problems.

What are you working on next and how soon can we pick it up?

I’m working on another book. But I think I’ve only written two things that are good enough for it. Since my last book came out, I’ve probably written 12 things [and] I think three of them are good enough. The other nine are fine, but they are not good enough for a book.

How do you figure out what’s good enough and what’s not?

I just feel it. I wrote an essay a few months ago and I feel strongly that it’s the best thing I’ve ever written. I didn’t need an audience to tell me that, I felt it. It’s not like I have a formula and I can sit down and do it again, it just sort of happened. I would like more essays like that before I [publish a new book]. Because if I were to put out a book and I had three essays that are good and 13 that were just okay, I can’t expect people not to notice that. And if people notice it, they’re going to say, ‘Obviously, he doesn’t really care anymore.’ And that’s the worst that can happen: not to care anymore. Then you should just stop.

You don’t want to lose your passion or your drive.

Right. But I think it happens to people all the time, especially when they become comfortable.

So you have to become uncomfortable again?

That’s the good thing about travelling. All of a sudden, you’re not in your comfort zone and you’re not getting special treatment because people recognize you. I don’t like to do things in order to write about them. Let’s say if I would get a job in McDonald’s so I can write about it, it’s just fake. I just don’t want to have inauthentic experiences and then write about them. It’s different, too, because I’m here [in Lahore] because I was invited so that’s always different than buying a ticket. It just changes the circumstances of the visit. It doesn’t mean that I can’t write about it, I just have to write about it differently.

What inspired you to start travelling? When did you start travelling in earnest?

I have a list called ‘countries I have been to.’ And then I was trying to get to two new countries per year, but then I got slowed down during the pandemic. So, Pakistan is my 58th country, but I really want to get to 100. I feel I really have to step on it. I’m 67, I got to get going here. And I just travel with different people. Some people are great to travel with, some people are just… they’ll just slow you down or are just not interested in the same things.