Ravi Riverfront City: Three years, two govts later, farmers in Punjab still struggle to save their land

LAHORE: On August 1, Colonel (retired) Abid Latif, director of public relations at the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA), proudly declared in a video posted on X (formerly Twitter) that his latest project was nothing short of a “piece of heaven” on earth.

That so-called “heaven” is Chahar Bagh, a luxury housing development sprawling along the banks of the river Ravi. Now 70% complete, it promises a mix of villas, towering skyscrapers, mid-rise apartments, and high-end condominiums. While one-kanal homes in Chahar Bagh are priced at Rs24 million, according to RUDA’s website.

The development also boasts futuristic perks like deliveries via drones and quadcopters to residents.

But Chahar Bagh is just the beginning. The Punjab government has far grander ambitions: to create the world’s largest riverfront city on the outskirts of Lahore and Sheikhupura.

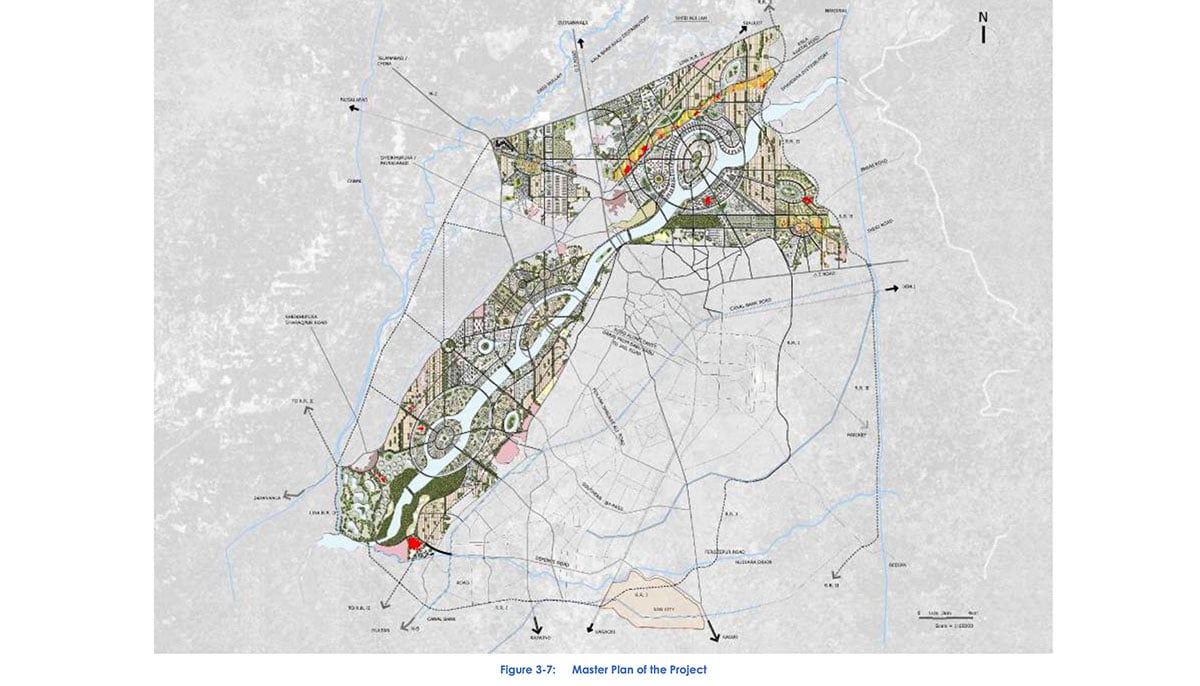

Covering an enormous 110,000 acres, the envisioned metropolis would house over 10 million people and feature medical complexes, sports arenas, entertainment hubs, government offices, and even an international airport. In 2020, the Punjab government established an exclusive development authority, called the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA), to oversee the new mega-city’s development.

But beneath the allure of luxury homes and shimmering skyscrapers, a harsh reality is taking shape: the sacrifice of fertile farmland.

A new city built on prime agricultural land

A 2021 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report, prepared for RUDA, disclosed that an overwhelming majority, therefore over 75%, of the land earmarked for the riverfront city is agricultural, where crops like wheat, rice, corn, and fruit are grown.

“The area along Kalakhatai Road is famous for producing Basmati rice, which is highly prized in international markets,” the report highlighted. Additionally, the development area includes seven forests, it noted.

The report further warned that most of the agricultural land “will be permanently lost and highly reduced after the project.”

Food security is a major concern for Pakistan. A 2024 report of the Global Hunger Index (GHI), a tool used by international humanitarian agencies to track global hunger levels, has classified Pakistan’s hunger levels as “serious.”

Yet, successive governments—first under former prime minister Imran Khan and now under Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif—have pressed forward with plans for the new city on arable land.

Punjab Chief Minister Maryam Nawaz Sharif and her father, Nawaz Sharif, have both recently visited the project sites, pledging close oversight of its progress. The idea of the riverfront city actually dates back to 2013 when then prime minister Nawaz Sharif first proposed it, though it lay dormant until 2020 when Imran Khan revived the project with considerable fanfare.

Since then, Punjab government officials have invoked the colonial-era Land Acquisition Act of 1894 to acquire land from farmers. And those who resist face severe consequences, such as imprisonment, eviction and being slapped with terrorism charges.

“Since 2020, the authorities have criminally charged more than 100 farmers with resisting or refusing to hand over land they occupied,” the New York-based Human Rights Watch wrote in April 2023 about RUDA. “Accounts by farmers, supported by photographs and video, provide evidence of intimidation, harassment, and use of force.”

Land acquisitions and legal battles

One such farmer is Sajjad Warraich, whose family owns nearly 500 acres along the Ravi in Sheikhupura. The land has been in their possession since 1945.

Warraich first learned of the new city’s plans in 2020 when then-prime minister Imran Khan visited his area to unveil the project. “I thought the prime minister was coming to announce support for struggling farmers,” Warraich recounted in an interview with The News, sitting at his farm, “Little did we know he would ask us to sacrifice our land.”

In 2021, Warraich and a group of farmers took their fight to court, winning a temporary reprieve, when on January 25, 2022, Justice Shahid Karim of the Lahore High Court ruled the RUDA project illegal on multiple grounds, including the lack of a master plan and the absence of local government approval.

“The conversion of farmland to other uses presents a real and present danger to food security, the environment, and social well-being,” the judge wrote.

But the victory was short-lived.

Days later, the Supreme Court of Pakistan partially suspended the High Court’s ruling, allowing RUDA to continue its development on land it had already acquired. Two years later, the case remains in legal limbo.

In the meantime, RUDA has not backed down.

Over the past three years, Warraich has faced five police complaints, some under anti-terrorism laws, for refusing to surrender his land. He has spent time in jail, had his equipment snatched, and seen his home raided by police. His youngest son even spent a month behind bars for protesting.

More recently, Warraich discovered that the government had allocated his private land to itself on paper—an act he claims directly violates the Supreme Court’s order. When intimidation failed to sway him, officials attempted to buy him off, offering an open-ended sum, he said. Warraich refused.

“For as long as I’m alive, I will continue to fight for my land,” the farmer vowed, hopeful that the Supreme Court will eventually rule in his favor.

Tahir Warraich, a 60-year-old farmer, shares a similar story.

He owns 43 acres of land along the river, which has been taken over by RUDA. In 2023, he brought the matter to court, where Justice Shahid Karim of the Lahore High Court ordered RUDA to allow him to cultivate his land. Despite the ruling, Warraich has been denied access to his property.

“They don’t let me into my own house,” an emotional Warraich told The News over the phone. “Every time I step onto my land, the officials abuse and threaten me.”

RUDA’s response: Development or Displacement?

Despite the legal battles and protest by farmers, RUDA has continued work undeterred.

To date, it has acquired around 13% of the total land needed for the new city—approximately 12,000 to 15,000 acres, according to Colonel (r) Abid Latif, RUDA’s director of public relations.

Of this, 2,000 acres, belonging to about 470 farmers, were acquired using the controversial Land Acquisition Act, he said, further claiming that the majority of the farmers agreed to sell their land to the state.

“Only 70 or so [farmers] are resisting it,” he told The News.

In recent years, and after orders from the Supreme Court, Latif claims that RUDA has also altered its land buying model and now offers market rates to willing sellers. “If the owner wants to sell, we buy. If they don’t, we don’t,” he said.

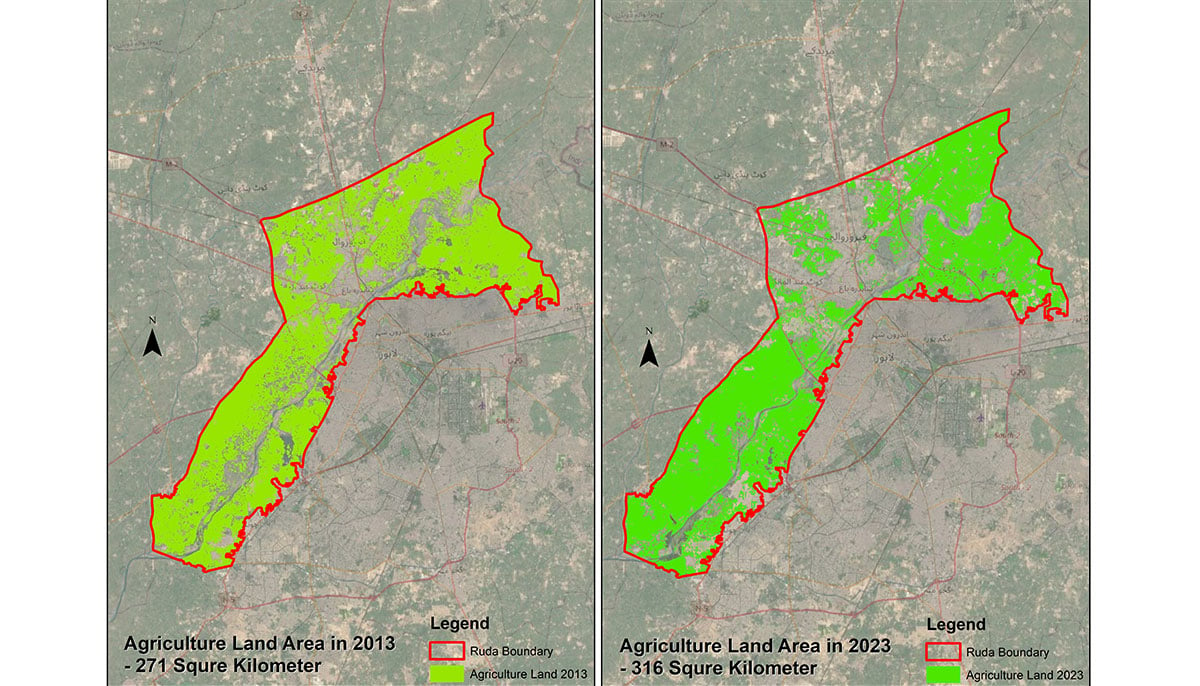

He also disputes the claim that 75% of the land is agricultural, insisting the number is far smaller and insignificant. However, when The News asked him to corroborate his claim with data, he did not respond. It must be noted that the government’s own 2021 Environmental Impact Assessment report calculated the fertile land to be more than 75%. The same figure was confirmed by satellite maps provided by another department of the Punjab government, which asked not to be named due to the sensitivity of the matter.

Below are satellite images of the land RUDA plans to build on taken in the year 2013 and then in 2023, which clearly shows that an overwhelming part of the marked land is agricultural land.

As work progresses, 30 companies have applied to construct housing societies in the new city, of which three have received a final go-ahead from RUDA, the retired colonel said. “[The new city] will also include a portion [homes] for the low-paid,” Latif insists, dismissing criticism that the new city was only for the affluent.

Among the various housing projects RUDA envisions, one stands out: “Maskan-e-Ravi,” a development that aims to provide affordable housing for journalists. Offering three to seven marla plots, the scheme has already attracted over 1,500 applicants from the Pakistani media, according to RUDA’s online portal.

Will the new city address Lahore’s housing crisis?

For RUDA, the new city is an urgent need to address Lahore’s housing and infrastructure challenges.

With a population of 13 million, Lahore is already struggling to cope with growing urban demands, it insists. “The only way forward is through a [new] planned city” adjacent to Lahore, reads a statement on RUDA’s website.

But urban planners remain skeptical, noting that luxury homes do little for low- and middle-income families living in Lahore, who are already struggling to find affordable housing.

“Who are we building this city for? Who will come and live in these apartments? Are we catering for a housing demand or are we catering for land development as a form of investment only?” asks Fizzah Sajjad, an urban planner based in Lahore.

The majority of demand for housing is for affordable housing, she added. “These exclusive villas won’t meet that need.”

The Punjab government, however, says that impact of climate change, the “inconvenience” to farmers, and issue about their rightful compensation will be “carefully weighed” against the needs of urban planning, particularly in light of population growth and city density.

“We are striving to balance these factors while ensuring that all actions are carried out within the framework of the law and justice. No landowner will be deprived of their legal rights or fair compensation, as stipulated by law,” a Punjab government official who asked not to be named told The News.

Home, but for how long?

Back on the banks of the Ravi, on a sweltering October afternoon, Sajjad Warraich sits beneath a large mango tree outside his home, where he lives alone with his wife. Local farmers gather around him in a circle. For them, Warraich is a hero - a leader who will lead their fight.

Despite struggling for three years, many of the farmers still hold out hope for justice from the top court. Warraich shares their optimism, though his recent petitions in various courts for an early hearing have gone unanswered, he said. “I don’t know what will become of me,” Warraich adds quietly, “I don’t even know if I’ll be here a few years from now. But those planning this new city need to stop and think about the future generations. They need to think hard: What are we leaving behind for our children?”

His words hang in the air, heavy with uncertainty—just like the status of the land he’s spent years trying to protect.

Originally published in The News