Living the secret silver-stamped life of Karachi's elusive Bihari chaapa

The chaapa sari is scarce in Karachi, and its subtle presence in a city where it is not native adds to its intrigue

By Duaa Amir

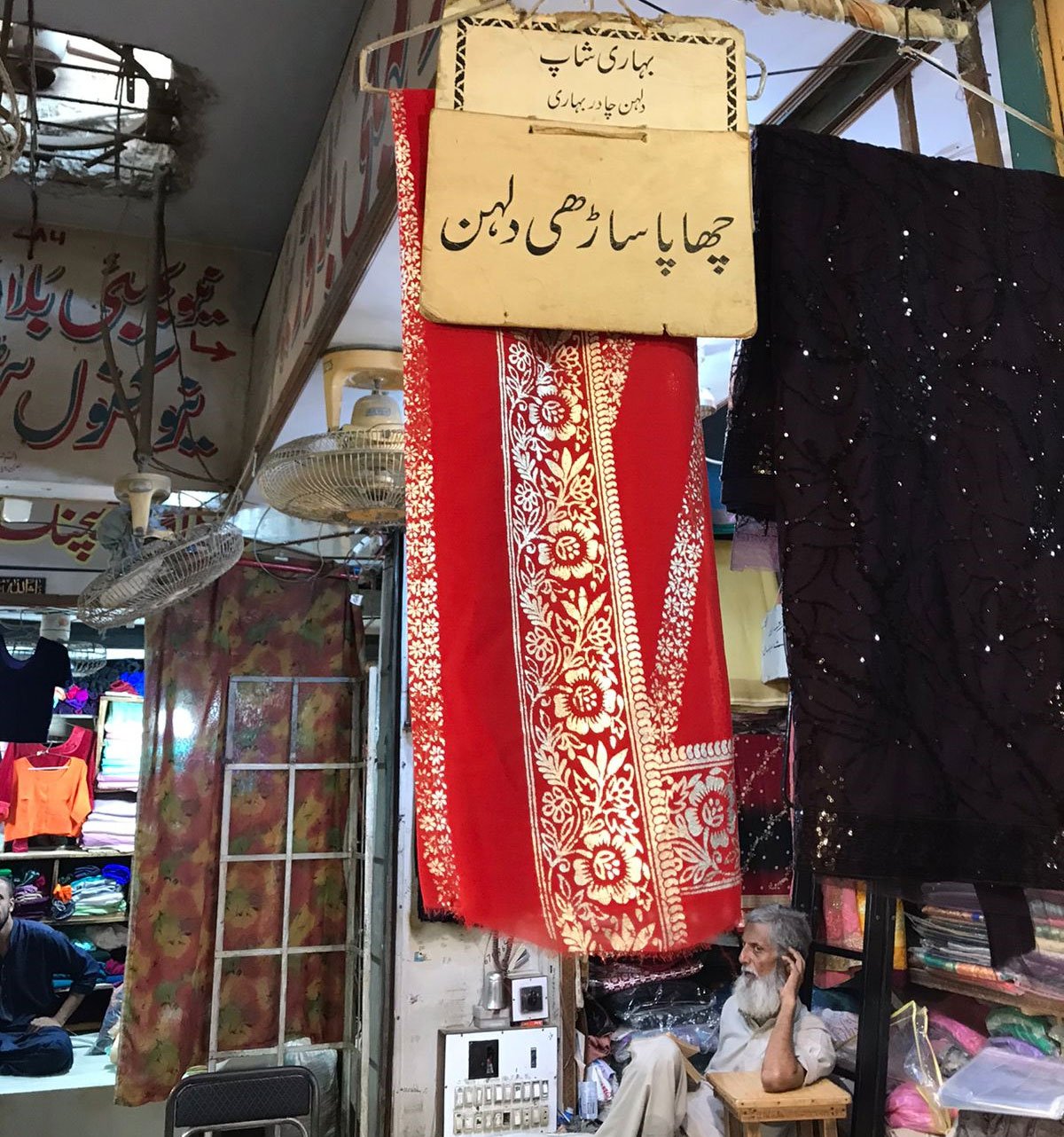

The elusive Bihari chaapa sari is seldom on display in Karachi's markets, where shops primarily showcase banarsi, kamdani, silk, and georgette saris — but if you ask a salesperson, they'll likely retrieve a single chaapa piece from a secluded corner. Let's find out why.

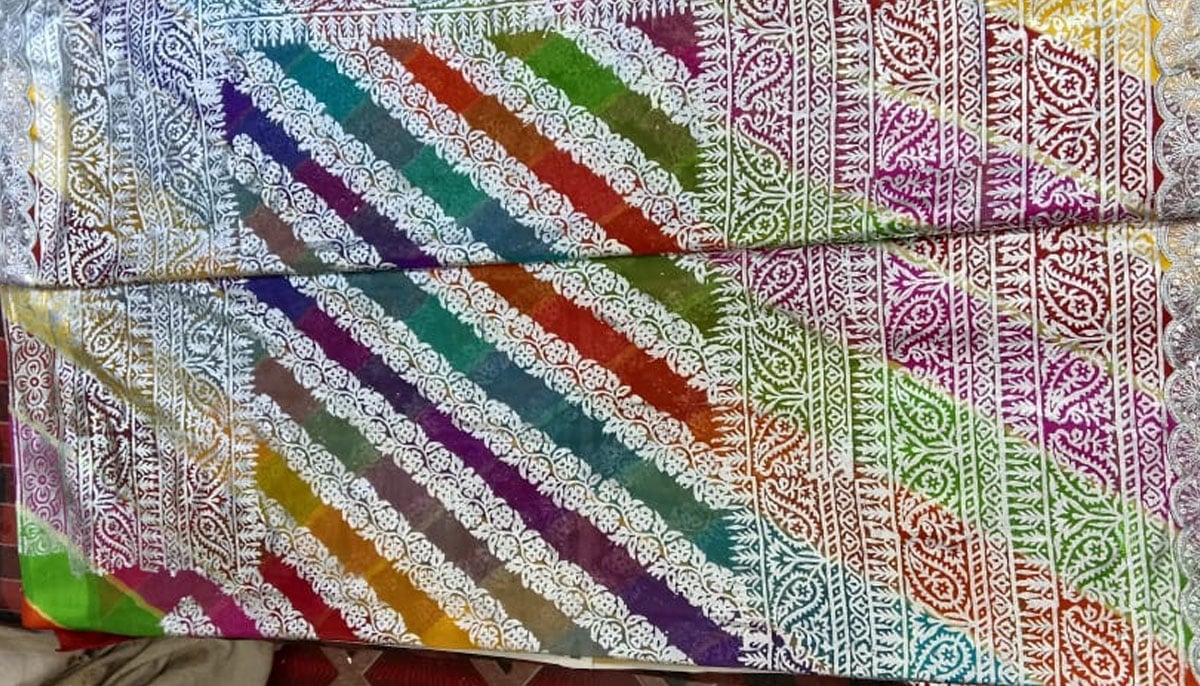

Carefully folded and covered in a plastic bag, the red chaapa sari looked beautiful. It reflected the silver foil work on it; repetitive patterns of motifs forming a lattice. The sari stands out because of its colour and the silver shimmer but also because of its unconventional nature.

Chaapa sari is not abundant in Karachi; nor does it have to be. Just its very existence in a city that it is not indigenous to and where it’s mostly kept hidden is intriguing.

What is chaapa?

Chaapa is a piece of hand-printed cloth that can be traced back to Bihar in India and has been a marker of cultural significance for different Muslim Bihari communities across the globe. The existence of chaapa can be dated back to the nineteenth century wherein a journal owned by Francis Buchanan mentioned the chaapa and its significant demand among the Muslim Bihari families in 1811-1812.

Since then, chaapa has continued to find a prominent seat at most Bihari wedding ceremonies. On the contrary, it can also be used to gauge one’s Bihari-ness. Do you know what a chaapa is? Then you’re a Bihari! But do you own a chaapa? And if the answer to this is yes, then you are truly the saviour of a Bihari heritage that has long been disparaged.

Despite the sari being the most prominent chaapa dress, the craft can also be done on just about any piece of cloth. Thus, it takes up different forms according to the occasion and preference. Chaapa dupatta, shalwar kameez, gharara, pillow-covers and even dulaai — a type of blanket made from two to three layers of cloth — are also very popular.

Shops in Karachi advertise this piece of cloth as 'Bihari-chaapa' and not just 'chaapa'. Therefore the place where it originates from is a crucial part of its identity. Even after years of chaapa being made in Karachi, it could never attain the distinction of a 'Karachi-chaapa'.

The origins of chaapa can also be attributed to a time of socioeconomic distress. According to some people, chaapa signifies the ease with which a bride could dress up back in the day. Chaapa looks beautiful and is less than half the price of a typical fancy party-wear. It is almost always worn as a sari during the nikah — so it is made to fit your body. The inclusive nature of this cloth makes it unique.

Visually, a chaapa resembles a block print. The scope, technique and therefore the feel of this cloth, all largely differ. The block print uses a liquid paint, whereas the chaapa is made from silver foil sheets called Tabak. The most original and authentic chaapa is shiny — but also a little stinky.

This way, the first sense that the original chaapa alludes to, is your sense of smell. The smell is most likely to enter your nose before the chaapa enters your visual field. In the current times, the smell has died down by a mile. It is difficult to tell if this was a collective conscious effort — or if the quality of raw materials is not at par with what it used to be, that has led to this change. Regardless, the Bihari community has taken this as a win.

From the other side of the border

When contacted by phone, Md Noshad Monami, a chaapa artisan from the Gaya city in Bihar, India, immediately inquired about the types of chaapa being crafted in Karachi.

"Can you tell me about the kind of chaapa being made in Karachi?" asked Monami from the city beside the Falgu River in the northeast Indian state of Bihar.

He was curious about the presence of this craft in Karachi, about the techniques and the designs, but most importantly how something native to Bihar was now being made more than 1500 kilometres away.

Now working in a shop where his father, uncle and grandfather worked before him, he takes a lot of pride in his work. For him, this craft was something that he attained after trying to learn and perfect it for a very long time. "As a kid, I was very enthusiastic about this. I used to see my elders make chaapa. I would look and memorise their steps in my mind —and now I can make the fanciest of pieces."

He now has two shops in Gaya, with his chaapa dresses being delivered all over the world. It is especially the chaapa palazzo pants — trousers with a wide-legged flare — that are quite the rage these days, Monami shared. On my query, he carefully listed out the steps of chaapa-making as well.

"First we take gond (glue) from a small dish that’s kept in water and then on a coal stove, and apply it on our hands."

"Then we take the block and apply the gond from our hands onto it. The block is then patted across the cloth on the table"

"Lastly, Tabak is pressed onto the cloth using a fist-sized ball of cloth." Tabak are thin sheets of silver that are the main component of the chaap. It is what gives the chaap a silver, shiny look.

"Even though it is a three-step process, it requires a lot of hard work," Noshad tells me. Maybe this is why, even in Bihar, people have started moving towards the screen-printed chaap. But the original chaap is here to stay according to him. He is not sure if his kids will enter this line of work but he is sure that the chaapa will continue to live on. Because in Bihar, Muslims can just not get married without the chaapa. "Yeh laazmi hai (This is essential)."

Another artisan from Patna, Bihar tells me: "Yeh jo mehak hai iska, yahi iski khubsurti hai (the fragrance that it has, is what makes it beautiful)." And I nod vehemently. He goes on to elaborate that not only is the business good for them, but he is also positive that the art of chaapa is going to survive and flourish because of its high demand.

Chaapa artisans in Karachi

The Bihari chaapa was not among the first items to reach Pakistani soil after partition. It was only years after 1947 that many Biharis in Pakistan began seeking chaapa saris for their weddings. As the border grew more rigid over time, obtaining a chaapa sari from Bihar became challenging, creating a gap in Karachi’s markets.

"My father started making chaapa and then he assertively made me enter the business as well even when I did not want to. Now when it’s a source of earning for me, I have fun doing it." Imran Baig, a chaapa artisan from Lalukhet told me.

He has been involved in this work for the last 30 years, making chaapa on custom orders from a small secluded shop. According to him, the chaapa made in Karachi has changed over the years; the visual appeal has remained the same but the technique has evolved. "Yahan chupaai nahi chapaai ka kaam hota hai (Here, it is about concealment, not printing)," he said. Which was to emphasise the secretive nature that this craft has taken up here. Artisans fear replication and scrutiny in an already competitive economy and therefore refuse to showcase their work on camera.

Business for him is as usual but he is not sure if his kid will learn from him and continue this craft. He just hopes that it does not become obsolete.

"Everything has modernised now. So has the chaapa. Around 90% of the time, the silver print does not come off!" Zaki, a middle-aged shopkeeper at Karachi's Hyderi market tells me. This was further confirmed by Jamal, also a shopkeeper in the same market, who said that the cloth was now washable. This is in stark contrast to the chaapa being made in Bihar which comes off even with the slightest bit of moisture. You cannot wear it more than three times.

The wooden carved block has also been replaced by a mesh stencil in some places that is used in screen printing, as told by Jamal. The screen-printed chaaapa closely imitates the block print work but it has greater precision and neatness. While it’s less labour-intensive, it lacks the hand-crafted look that defines the original blockwork chaapa.

Future of chaapa

For a long time now, the chaapa has been criticised, because of its smell but most importantly because of its association with the Bihari migrants. As a consequence, chaapa has been worn discreetly, or worse, has been shed by second and third-generation Biharis in an attempt to overcome criticism. However, this trend now seems to be changing.

Despite the evident differences in the process of making chaapa across the border, the lived experiences around the cloth have hardly changed.

"It smells kind of funky in the start but if you’re a true Bihari then you know it’s not funky," Zehra Khan, a Bihari living in Karachi, tells me.

She was dressed in a chaapa when she was born but is set to wear a chaapa again on her chauthi when she gets married.

Afzal Adeeb Khan, a photographer from Bihar, India, echoes similar thoughts.

"The only thing I dislike about chaapa is that it stinks a lot. Even the thought of going near someone in a chaapa was traumatic! Nowadays, artisans use different chemicals, so the smell isn’t as bad," he said.

Three years back when his sister got married, she dressed up in a red chaapa sari as well.

This goes on to highlight how chaapa is an important cultural symbol, especially in weddings, But there has been a shift towards its use more casually, as Zehra reaffirmed.

This also comes as a necessary step by the Bihari descendants in Pakistan — who now want to own the chaapa because of its cultural significance. The chaapa defies the South Asian idea of fancy cloth, in terms of style and handwork, weight and cost — and so even if you’re not a Bihari, you might want to give it a go.

Chaapa in Karachi may have been birthed out of need, unlike the chaapa in Bihar which is both a tradition and a legacy. But its persistence despite the odds is reason enough for it to not be hidden away; in the markets of Karachi and as a part of one’s cultural identity.

Duaa Amir is a writer based in Karachi. Her work revolves around the food and culture surrounding migrant identity. She posts on X @duaaamir9 and on Instagram @duaa__amir

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv