The fifth season: How smog is gagging life, livelihood, and culture in Lahore

Lahoris are caught between changing climate trends, a reactionary government, and unchecked emissions—something must change

Every day, as Lahoris wake up, their hands sleepily gravitate towards their phones. They do this not to check WhatsApp messages, but to check the Air Quality Index (AQI) in the city. This daily act, filled with anxiety, marks the arrival of "Smog Season 2024", the worst yet. Days with 1,000+ AQI levels have not only increased in frequency but are becoming the new normal. How does one react to such a reading? How does one prepare when the light streaming in is tinted brown and grey?

There's little control over the air, but when the most basic requirement of life is filled with toxins, one feels helpless. People in Lahore — and, as of this writing, in Multan — must decide how to live amidst some of the worst air pollution on record. Life goes on, but residents face an impossible choice about how much they must choke to keep living.

Aneeqa, who lives in Lahore’s Model Town, has been raised around parks, greenery lining the roads, and outdoor Sundays, come rain or shine — or smog. Part of a large group of bicyclists who cycle various city routes, Aneeqa woke up at her regular 5am on Sunday, November 3, to prepare for her ride. She noticed some fellow cyclists dropping out due to feeling unwell but shrugged it off. Outside her door, she would face the city’s worst smog day.

With reports of AQI readings over 1,900 making headlines worldwide, Aneeqa chose to ride but quickly regretted it. "We had covered half our route when I started feeling dizzy and almost nauseous," she shared. She had to stop cycling, and as breathing became difficult, she was rushed to the hospital for a severe allergic reaction to air pollution.

“Every year we have smog, and I thought I shouldn’t let it confine me. This is my city. I love riding my bike in this weather, but it's unsustainable. It's too hot in summer, and now fall — and possibly winter — will choke us. What do we do?”

Restricted ambitions

This environmental hazard also affects Rukhshan, an outdoor enthusiast currently training for long-distance running. His regimen, which includes running and football, has been severely affected by the smog.

"I have to check the AQI each time I go out to run. Anything above 800 is out of the question, so I’m forced to train on a treadmill, which isn’t optimal," said Rukhshan.

He noted that all the running events he had signed up for in the past three weeks were either cancelled or postponed due to smog. "People are signing up less or cancelling plans. Even for football, fewer people are stepping out, either by choice or because families stop them."

The intensity of this year’s smog raises questions about its causes and why it worsens yearly. Dawar Hameed Butt, the director of Climate Finance Pakistan and co-director of the Pakistan Air Quality Initiative, shared insights on Lahore’s unofficial fifth season. He defines the phenomenon through two factors: regional weather changes and human activity.

"We have data showing it’s getting worse. The 'cleaner' monsoon season is getting shorter and more unpredictable, partly due to climate change, allowing pollution to gather post-monsoon. Additionally, population growth drives emissions, and this year, the industry picked up after two years of a slowdown."

On stubble burning, Dawar noted it usually occurs in early November. Smog outside this window is attributed to "local sources" like car emissions, factories, and general activity.

Economic pressures

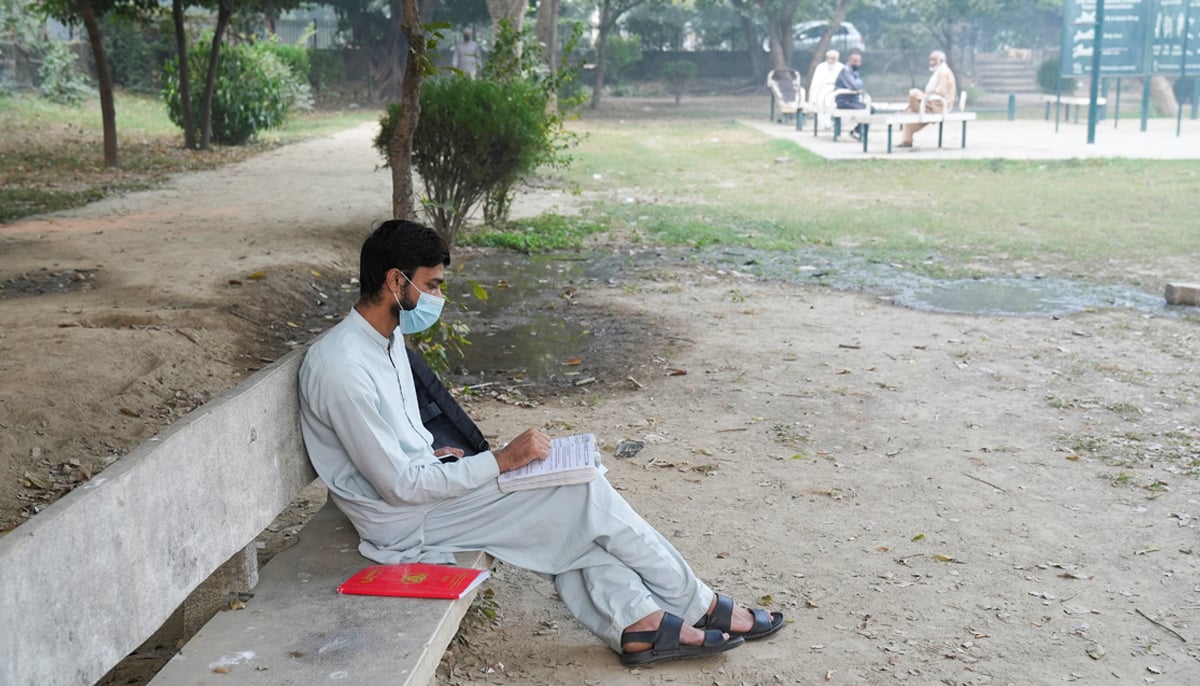

For some, staying inside is an option, but a large population must work outside. Smog poses the greatest risk to this segment, where inhaling toxins is tied to earning a livelihood.

Irfan*, a caddy at a private Lahore golf club, cherishes October and November, his favourite months.

"The heat disappears, and mornings on the dewy green are perfect. Now it’s horrendous." Irfan’s job revolves around when the elite play golf. "It’s admirable they play in these conditions, but it’s a choice for them. If I say I can’t work because the air makes me sick, I’m replaceable."

Open-air areas have since closed in Lahore’s smog "hot spots," including Irfan’s club, which shut for a week.

"What can I say? I go and breathe smoke; if I stay home, I worry if the club will pay me." Reflecting on last year’s closures, Irfan recalled that clubs weren’t transparent on how shutdowns affected wages for staff like him.

October to December was once a festive season in Lahore. The domination of smog now brings a sense of loss. Ghazi Taimoor, a social entrepreneur, operates "Lahore Ka Ravi", a venture educating people about Lahore’s history through guided neighbourhood walks. "September to November is when Lahore is at its peak. With the smog, we’ve had to cancel so many of our planned walks."

Public gatherings are now impacted by city-wide “green lockdowns,” marking the season with uncertainty. "From cancelled classes to postponed walks and corporate commitments, planning has become challenging."

Halted work and uncertain pay

Amjad, part of a construction crew on Lahore’s outskirts, pauses at the sight of smog, worried not about his health but his earnings. "Last year, they stopped construction at another site I worked at. The contractor sent us home without pay. I only know this work; where would I go if they stop construction?"

Work delays ripple into timelines, pressuring crews to make up time as if construction never paused. "Owners want projects completed on time, which means earlier starts or late finishes. We’re rarely paid for this extra time, let alone fairly."

When it comes to schooling, the government’s stance on smog prioritises children’s health. Sana’s five-year-old son, who attends a private school, has been home due to a green lockdown.

"It just feels like a lazy solution," Sana laughed. "I would happily keep him home if I saw other steps being taken. They’ve closed schools, but just outside Lahore, factories are spewing toxins, and stubble is burning."

Not all children benefit from online schooling. Asiya and her husband, both cleaners, have two children whose low-cost private school has no virtual setup.

"Not every home has a smartphone for online calls," Asiya shared. "We leave in the morning, and the children are with their grandmother. We tell them not to play outside, but they’re kids. This lockdown doesn’t help."

Economic and health inequality

For people like Irfan and Rukhshan, smog impacts health and limits outdoor access. For Asiya, Sana, and Amjad, it’s a nuisance with economic and household repercussions. For others like Aneeqa and Ghazi, smog diminishes their connection to the city they love. Each group confronts smog’s impact daily, but the burden varies by economic and social status.

If smog has become inevitable, what has been done about it? Dawar noted the government’s first intervention came in 2016, and every administration has taken reactionary measures since.

"They haven’t tackled the sources of pollution. Their approach is administrative, such as imposing bans and FIRs, which is ineffective since pollutants are already airborne."

The government started green lockdowns with schools, prioritizing children as the most vulnerable. This action highlights a dichotomy in schooling experiences, showing how policies can be experienced differently across social lines.

Dawar contrasted Lahore’s situation with Beijing’s smog recovery, where the government enforced a zero-tolerance health policy. "A Beijing-style recovery would be hard here due to resources and political commitment. Punjab lacks both the funds and commitment for a dedicated air pollution effort."

Lahore continues to choke under heavy air pollution. Air quality, once a public concern, is now an economic issue, determining daily quality of life. Lahoris are caught between changing climate trends, a reactionary government, and unchecked emissions — something must change.

This smog season shows that "business as usual" is no longer sufficient. The volatility in the climate and ever-increasing emissions cannot be accepted as mere realities. Inaction is unacceptable. If cities like Lahore and Multan can endure AQI levels above 1,900, unchecked climate change could bring even greater calamities in the future.

Arslan Athar is a writer based out of Lahore, Pakistan. He was a 2021 South Asia Speaks fellow, working on his novel with mentor Fatima Bhutto. Arslan's fiction and non-fiction work has been published in numerous national and international publications. He posts on X @ArslanArsuArsi

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv