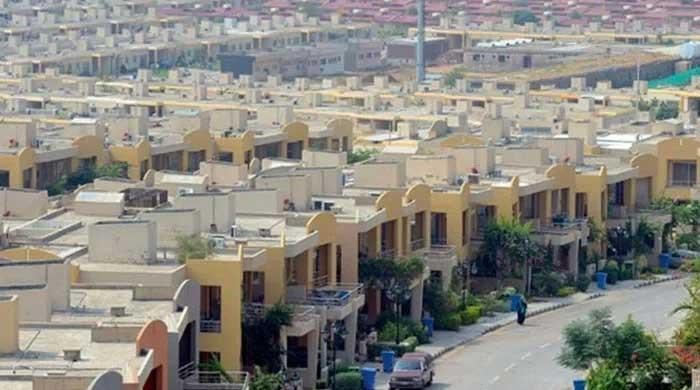

Karachi Climate Action Plan: What you need to know

Celebrated as the city of lights, it distressingly falls under the looming darkness of climate crises

December 20, 2024

Karachi, a city rich in ethnic, religious, and cultural diversity, faces an equally diverse range of climate change threats, pushing it toward a critical tipping point. Prolonged heat waves, delayed winters, urban heat island effect, erratic rainfall, flash flooding, air pollution, waste pollution, water scarcity, sea level rise, drought, etc.— the city has been bearing repercussions for each of the risks and vulnerabilities. Celebrated as the city of lights, it distressingly falls under the looming darkness of these crises. Both citizens and the public sector share responsibility as culprits and victims of these vulnerabilities. As nature retaliates, it implores our consciousness to act immediately.

Despite growing awareness of these climate crises, real action has remained elusive. There is a notable reluctance among the entities to move beyond words to real, impactful changes, raising a crucial question: Can real progress occur when acknowledgment of the problem lacks the resolve to act. Restoration can be pursued through specific strategies, but the fundamental challenge lies in the lack of genuine commitment and accountability to implement meaningful actions.

Recognising these pressing issues, a significant yet largely unknown effort is underway: the Karachi Climate Action Plan (K-CAP). Interestingly enough, despite being a megacity where everything quickly reaches the public and dominates media discussions for days, regrettably, it would not be wrong to state that the public has largely remained uninformed about this from the beginning.

For the very first time, the K-CAP is being developed under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in collaboration with its partners C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40), the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) as the implementing agency, Unit Punjab serving as the consultant, and NED University acting as the advisory body to the consultant. C40 is a group of nearly 100 mayors from major cities around the world, working together to tackle climate change and cut emissions by half by 2030.

The plan began in November 2023, with multistakeholder meetings and workshops. Expected to cover an entire duration of eight months, it is still set to launch, with the latest reported timeline being December 2024.

The plan includes a total of nine deliverables labeled ‘A through I’. Beginning with Strategic Appraisal, Vision Development, and Need Assessment which is the evaluation of Karachi's current climate targets, policies, and actions, identifying gaps, and proposing efficient strategies to align its plan with the C40 Framework and Paris Agreement targets.

The plan includes Karachi's Green House Gas Inventory, analysing emissions across key sectors—Stationary Energy, Transport, and Waste—and identifying sources of emissions. Further, it incorporates Emission Modelling/ Pathways/ Scenario Mapping to establish actionable pathways to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, which means balancing between the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) was also conducted, highlighting the city’s climate risks prioritised, such as urban flooding, coastal flooding, urban heat stress, air pollution, and drought.

The plan focuses on devising Adaptation and Mitigation goals and targets plan (Deliverable E) to deal with identified risks and threats. A few actionable projects (Deliverable F) have also been identified and prioritised for implementation.

The Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting (MER) Plan (Deliverable G), which currently includes a proposed MER Framework, incorporates key sectors in its indicator matrix. These sectors include Building, Energy, Industry, Transport, Urban Planning, Waste, Air Quality, Adaptation, and Cross-sector, to track and assess the progress of the implementation of the KCAP.

The proposed Climate Governance Framework under the Climate Action Governance (Deliverable H) suggests changes in the local governance structure, including amendments to the Sindh Local Government Act, 2013, to incorporate the environment as a subject, and the establishment of a Directorate of Environment and Climate Change (DoECC) and a Climate Change Board (CCB) within KMC. Eventually leading to the Climate Action Plan (Deliverable I). As the plan approaches completion, only a few deliverables (A to D) have been made public, pending approval of the remaining deliverables (E to I) by the authorities.

The consultations for the multistakeholder meetings and workshops did not appear satisfactory. Meetings with government agencies and civil society organisations, held in isolation, limited the broader aim of consultations. Despite the stakeholder consultations, many felt the process was more procedural than genuinely inclusive.

It seemed like their involvement was more about fulfilling the procedural requirement of consultations rather than incorporating their feedback and responses into the plan. One key stakeholder, the Climate Action Center Karachi (CAC), has remained actively engaged throughout the plan’s development, participating in consultations and suggesting ten areas for improvement, including low-cost electricity, electric transport, urban food forests, waste management, circular economy, green buildings, and youth engagement. CAC's ongoing efforts to remain involved have highlighted the need for more transparent and meaningful engagement.

Director of Climate Action Center Karachi, Yasir Husain, has highlighted the significance of engaging the public in the climate action plan. He believes it is crucial to incorporate community knowledge and foster public participation, or else the foundation of this plan will be tenuous in addressing the climate crisis.

On a positive note, CAC has found both the UNDP and KMC to be responsive and open to discussions, with both organisations willing to incorporate CAC’s recommendations into the plan.

Projects and plans developed and secured through international funding, often follow a generic pattern. Announcements are often made to a limited group, later referring to them as multistakeholder meetings and consultations to fulfill procedural requirements.

This approach often leaves the broader public unaware of the project’s progress, as key information is withheld until the plan is close to completion, often justifying this delay by the need to secure necessary endorsements before a public announcement, which can inadvertently limit the input of those who will ultimately be most affected by the plan.

In the void of public understanding and support, it would seem cliquish to develop a blueprint for a city without the consent of its citizens since such plans and efforts are deemed effective only when they reflect the lived experiences of the people it aims to serve.

Genuineness and commitment lie in translating the strategies and targets into tangible actions that resonate with Karachi's everyday life. Initiatives like the Karachi Climate Action Plan are a positive step forward. However, it is crucial to ensure that this plan, is a practical roadmap rather than a mere document that addresses the realities of Karachi's climate challenges, with conferences and meetings but without real consequences.

The K-CAP's progress has been slower than expected, but its comprehensive approach to addressing Karachi's climate vulnerabilities offers a crucial framework for the city's future. While the technical expertise of consultants is invaluable, the plan's development process, guided through tablework and discussions, is often easier than putting it into action, especially when consultants may not be intimately familiar with Karachi's unique challenges, which can risk missing critical perspectives.

To ensure inclusivity and effectiveness throughout the process, creating an environment where feedback from Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) and the public is encouraged and incorporated into decision-making is essential.

The success of the K-CAP requires more than just the efforts of government agencies and technical experts; it also depends on the active involvement of CSOs and the local community. It is highly suggestive that public participation through local and indigenous knowledge must be prioritised equally with multi-stakeholder consultations and meet-ups.

It is imperative to engage CSOs and community representatives from the early stages of the planning followed by carefully integrating their voices throughout each step to ensure that solutions reflect local needs and challenges. This ensures the process remains grounded in action, accountability, and transparent governance.

Warda Mumtaz is a climate researcher at the Climate Action Center, Karachi. Her work focuses on addressing urban climate challenges, fostering public participation, and exploring community-driven initiatives.