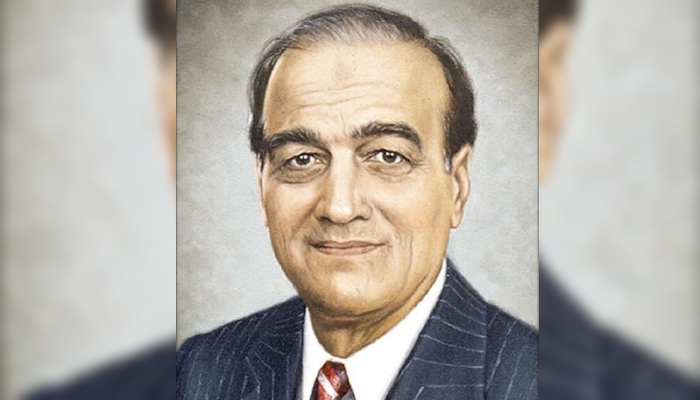

Mir Khalil-ur-Rahman: Visionary architect of modern journalism, voice of masses

"In early days of Jang, he took on every possible role. He reviewed newspapers, wrote editorials," says Arif

January 25, 2025

Mir Khalil-ur-Rahman, the visionary founder of Jang, was a man of exceptional qualities — an eloquent conversationalist, an astute journalist, and an inspiring leader. His charisma and sharp intellect left a lasting impression on everyone he met, whether they were seasoned journalists or aspiring writers.

Ariful Haque Arif, senior journalist who has a long association of 58 years with Jang and which still continues, says: “In the early days of Jang, he took on every possible role. He cleaned the office, reviewed newspapers, wrote editorials and edited articles, and even took photographs for publication. As a good reporter himself, he was committed to finding good stories and scoops for his paper.

“Two anecdotes illustrate his dedication to journalism. During General Zia-ul-Haq’s era, the National Assembly was replaced by a nominated Majlis-e-Shura, and a similar Sindh Council was formed at the provincial level. Mir Saheb was a member of the Sindh Council and attended its sessions regularly, presided over by Governor Sindh, General Sadiq Ibrahim Abbasi. Reporting on the proceedings was my responsibility. On one occasion, Mir Saheb glanced at the press gallery and assumed Jang’s reporter was absent, though I was there but went unnoticed. He took out his notebook and wrote important points. After the session, when he spotted me, he said, 'I took these notes thinking you weren’t there. Please use them if they can help you in creating a good report.' I was astonished to see the level of detail he had captured, documenting the entire session.

“Another incident occurred during a farewell dinner for Governor Sindh, Lieutenant General S.M. Abbasi, hosted by the All-Pakistan Newspapers Society (APNS). Speculation was rife that he would be given federal portfolio, and soon the news emerged that he had been nominated as the Federal Minister for Petroleum. Mir Saheb sat at the main table with other media owners and editors, while I sat at a distance. After the event, Mir Saheb personally dropped me at the office and remarked, ‘There’s an important story; wait for my call.’ Around 15 minutes later, he called and dictated an exclusive news 'The Governor had disclosed that he personally approved Nusrat Bhutto’s travel abroad.' The story was published the next day with prominence in Jang but no other newspaper carried it.

Shabbir Ahmed Siddiqui, senior journalist, broadcaster and a writer of a book “Sahafat se Sahafat tak”, who retired from Radio Pakistan as Controller News has vivid memories of having few meetings with Mir Khalil-ur-Rahman.

“My first interaction with Mir Saheb was in connection with a job after completing my Master’s in Journalism from Karachi University. My father’s close friend Qazi Muhammad Akbar, the owner of Ibrat, referred me to Mir Saheb who called me for an interview, which turned into a long and engaging conversation lasting two and a half hours.

“I must say, Mir Saheb was a gifted conversationalist. He possessed a unique ability to captivate his visitors with his eloquence and command of language. He steered the discussion so skillfully that it felt less like an interview and more like a friendly exchange between two long-time acquaintances discussing matters of mutual interest.

"While I didn’t get the job — he politely explained that there were no vacancies at the time — I left his office with an inexplicable sense of satisfaction, as if I had already secured a rewarding position at Jang Group.”

The role of Daily Jang in Urdu journalism, particularly in Pakistan and the broader subcontinent, has been transformative. Prior to Pakistan’s independence, Karachi was home to Sindhi and English newspapers, but lacked a good Urdu publication. After independence, with Karachi becoming the capital, the rise of Urdu newspapers like Anjam and Jang ushered in a new era in journalism.

Initially launched as an evening paper in Delhi, Jang, in pre-partition India, under the visionary leadership of Mir Khalil-ur-Rahman, evolved into a powerful institution and a training ground for aspiring journalists. Daily Jang has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on the history of Urdu journalism in the subcontinent.

“His success can be attributed to several core principles that he always held dear,” says Dr. Tauseef, a columnist, analyst, and educator. He adds: “First, he had an exceptional ability to identify and recruit talent within his organisation. For example, when Imroz ceased publication in 1958, several prominent journalists, including Ibrahim Jalees and Syed Muhammad Taqi, joined Jang.”

Dr Tauseef says, Mir Saheb also understood the importance of news and its presentation. He made huge sacrifices to ensure that news content and layout meet the best quality and standards. One of the major contributions of Jang to Urdu journalism includes the introduction of press releases, which reshaped how information was disseminated. By publishing statements from political parties, student organisations, and other groups, Jang provided readers with broader reach and perspectives of news.

“Mir Saheb’s commitment to technology set Jang apart from its contemporaries. In the 1950s and 1960s, Jang transitioned from yellow paper and basic layouts to clearer, more sophisticated and catchy designs which increased the visual appeal of the paper. It was among the first to use machines capable of transmitting photographs, even before the advent of computers and modems. This allowed Jang to print images in the paper from cities from around the globe.”

The decade of the ‘80s is said to be the era of colour printing and Jang took no time to adopt this technology. “In the 1980s, Jang revolutionised Urdu journalism by introducing Noori Nastalique, thus modernising the Urdu newspapers typesetting.”

Whether criticising flawed government policies or advocating for the oppressed and marginalised, Jang has always upheld its commitment to truth. During elections, it has diligently highlighted issues related to the candidates and their platforms.

“One notable example is from the presidential election between Fatima Jinnah and Ayub Khan in January 1965. Fatima Jinnah’s election symbol was a lantern, while Ayub Khan’s was a rose. Prior to the election, Jang published a special issue on Quaid-i-Azam’s birth anniversary. This issue featured a photograph of the Quaid wearing a white suite, with roses spread at his feet. Symbolically, this imagery reflected the pure and unblemished character of the Quaid’s sister or his family, with the roses lying under the feet of the Quaid as a sign of public displeasure for the other candidate that he is under the feet of the Quaid,” maintained Shabbir Siddiqui.

"This powerful message deeply reflected the public’s love and respect for Jinnah and his sister. It was yet another example of Jang fearlessly amplifying the voice of the people.

"Another critical factor behind Jang’s success was its inclusivity. “The newspaper presented a wide range of ideological viewpoints, incorporating columns and editorials that catered to different schools of thought, from the left to the right,” says Dr Tauseef.

A major milestone in Urdu journalism was Jang’s introduction of “interpretative reporting,” a style previously reserved for English newspapers like Dawn, he says.

“When Jang Lahore was launched, Irshad Ahmed Haqqani added another aspect of journalism-analytical approach-analysis of various news and views. Political and social issues were explained in depth, offering readers insights previously unavailable in Urdu journalism. Although Jang maintained balance by publishing contrasting views from columnists like Mujeeb-ur-Rehman Shami, Abdul Qadir Hassan, Munno Bhai, Ahmed Bashir, who joined Jang along with Irshad Saheb, the interpretative approach reshaped Urdu journalism and increased Jang’s circulation in an unprecedented manner,” says Dr Tauseef.

Jang’s ability to adapt to modern reporting styles while maintaining its traditional strengths helped it remain relevant in an increasingly competitive and changing media landscape, he adds.

“The 2007 Lawyers’ Movement, for instance, marked a shift towards bold, analytical reporting. Jang began publishing analyses by journalists on its front page, something not in vogue in Urdu newspapers. These analyses often critiqued sensitive subject. This evolution attracted readers who valued in-depth coverage and insightful commentary,” maintains Dr Tauseef.

Ariful Haq says one of Mir Saheb’s defining traits was his strict adherence to punctuality. His deep respect for time extended to all aspects of his life, from work schedules to social engagements.

“During a Faran Club reception, the organisers cleverly served meal before the event to ensure timely attendance. Impressed by their ingenuity, Mir Saheb devoted his speech to praising their initiative and emphasising the importance of punctuality."

Shahbbir Saheb says: “In my childhood, Jang was a two-ana newspaper. At that time, it was renowned for the contributions of Majeed Lahori, Raees Amrohvi, and B A Najmi. Majeed Lahori’s tongue-in-cheek columns were immensely popular, and Jang’s clever disclaimer that it did not necessarily agree or disagree with the views expressed by its columnists shielded it from any backlash. B A Najmi’s sharp and thought-provoking cartoons conveyed what words could not. Raees Amrohvi’s poetic couplets added a literary dimension that readers eagerly looked forward to. His poignant verses often reflected the mood of the nation."

Shabbir Saheb recalls that when the Daily News, the English evening paper of the Jang Group, launched, Wajid Shamsul Hasan served as its editor and writers like Qutubuddin Aziz, Jami Saheb, and Allama Tanveer (who later joined Dawn) contributed in the paper.

Shabbir Saheb shared an anecdote about Prof Lateef Ahmed, a witty political science professor at Islamic College. “One evening at Ampis restaurant near Karachi’s Metropole Hotel, Wajid Shamsul Hasan, Allama Tanveer, and Nizami Saheb discussed the next day’s headline, as it was a national holiday when evening papers gained prominence.

Prof Lateef, in charge of Hurriyat’s sports section, humorously referred to politicians Akbar Bugti, Ataullah Mengal, Khair Muhammad Marri, Sher Muhammad Marri, and Ghaus Bux Bizenjo, who were in London, and quipped, 'Is there a London Plan?' Wajid Saheb immediately chose it as the next day’s headline for his paper. The phrase 'London Plan,' was actually coined by Prof Lateef that remains in use even today."

Digital media and social media have undoubtedly played a role in the decline of print journalism, but this shift has also resulted in a severe compromise of objectivity. Dr Tauseef says that ensuring the survival of print media is not just the responsibility of journalists but also of the state, an informed society, and intellectual stakeholders.

“While the format of print media may evolve — possibly transitioning from paper to digital platforms — it should remain the most credible source for objective reporting. Debates on the survival and revival of print media must take place in newsrooms, universities, and press clubs across Pakistan,” he opined.

“During the crisis of 1971, when the Chittagong port was blocked, leading to a shortage of newsprint, the government under Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto imported affordable newsprint and distributed it to newspaper publications. This step, coupled with the nationalisation of industries and advertising support, helped revive the print media industry at that time. Today, similar strategic measures are required, including tax reductions, subsidies on electricity and other operational costs, and collaborative conferences involving journalists, workers, and media owners,” he maintained.

He also calls for reform in the reporting structure. “Strengthening editorial authority and promoting a culture of adaptability and objectivity are crucial to overcoming these challenges and ensuring the survival of print journalism in an ever-changing media landscape,” he concluded.

Originally published in The News