Peca's protection plan: Speak at your own risk

In the last few days, while dissecting the new Prevention of Electronic Crimes (Amendment) Act (PECA) 2025, it feels like déjà vu. It’s as if we’ve been transported back to 2015, a time when some of us were fighting against the original Peca draft, which contained draconian provisions.

Back then, digital rights activists raised alarms about the potential weaponisation of the law against journalistic work and its chilling impact on political activism in online spaces. I vividly remember how the IT Minister at the time, from Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), would dismiss these concerns, assuring journalists that their work would be protected under the law.

Since Peca’s enactment in 2016, we have witnessed the very fears we raised become reality. Dozens of cases have surfaced where journalists, activists, political dissidents, and even politicians have faced the weaponisation of Peca against them.

The law, originally touted as a means to protect the most marginalised and vulnerable in society, particularly young women and girls, has failed to deliver on that promise. Over the last nine years, the cybercrime wing has not been able to develop a structural or effective framework to address harassment, disinformation, or hate speech targeting Pakistani women, girls, women journalists, and politicians. Instead, we have seen the cybercrime agency and regulator, Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), demonstrate hyper-vigilance in suppressing content they deem "misfit".

The initial argument of protecting women was used as a shield to introduce a law aimed at controlling dissent and silencing content critical of the state. Today, a new argument has emerged: controlling fake news and harmful content. Interestingly, the proposed amendments define these terms so broadly and ambiguously that they could open the door to even greater misuse. Alarmingly, the amendments propose criminalising fake or false content, an approach fraught with potential for abuse.

When Peca was first introduced in 2014, two years of consultations took place, not because the government sought meaningful dialogue with stakeholders but because digital rights activists resisted the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill with all their might. This time around, the amendments were introduced without sharing a final draft with relevant stakeholders, let alone conducting any consultations. Despite hearing whispers about ongoing work on the amendments, no draft was ever shared with the public or stakeholders.

On January 23, mainstream media reported that the Peca amendments had been approved by all three major political parties in the National Assembly. By January 27, the Senate Committee on IT passed the draft in just 15 minutes, without debate. On January 28, the amendments cruised through the Senate with no meaningful discussion or opposition. Now, with a flick of his pen, the President of Pakistan will enforce the amended Peca law anytime soon.

As these broad amendments edge closer to becoming a reality, Pakistani internet users can’t just continue to use the internet the way they have been using it. While we are headed toward the path of greater criminalisation of speech, it is crucial to understand what this means for our digital lives. The consequences of these changes will shape how we engage online.

Can you go to jail if you intentionally post, reshare, or forward fake/false news?

Yes! Under the new amendment, any social media user who intentionally harms another’s reputation through fake and false news can face punishment of up to three years in prison and a fine of up to Rs2 million. This will be enforced by the new investigation agency called the National Cyber Crime Investigation Agency (NCCIA).

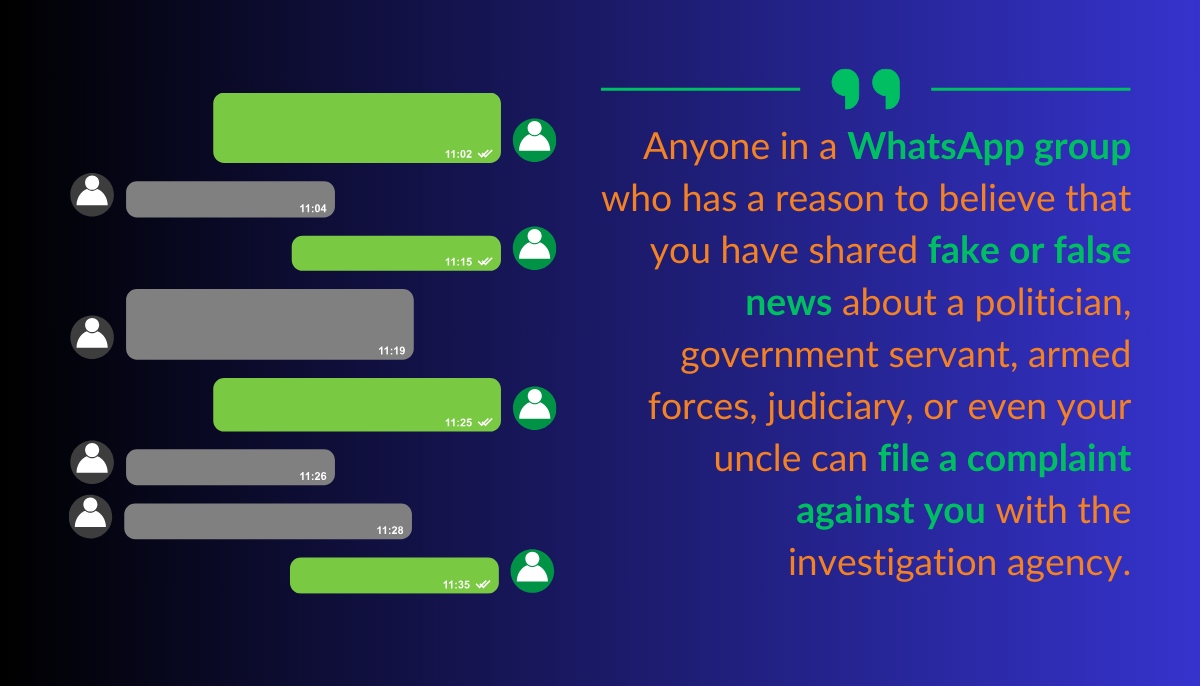

Until this new agency is established, the cybercrime wing under the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) will implement the amendments. Additionally, anyone can file a complaint against you if they have a reason to believe that you are spreading fake news to damage someone’s reputation.

Is WhatsApp considered a social media platform?

If you think you will be fine by being careful on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and X, think again! The definition of a social media platform is so broad that it includes WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, messaging apps, web platforms, and any other communication channel that allows you to create an account and communicate with others while generating content.

Now, go back to the last paragraph and read who can file a complaint against you. Anyone! This means anyone in a WhatsApp group who has a reason to believe that you have shared fake or false news about a politician, government servant, armed forces, judiciary, or even your uncle can file a complaint against you with the investigation agency.

Besides fake news, "illegal" content will also be regulated

The scope of illegal content now includes material deemed against Islam, the security or defence of Pakistan, public order, and content critical of constitutional institutions such as the judiciary and armed forces. The new authority, called the Social Media Protection and Regulatory Authority (SMPRA), will be tasked with removing or blocking "illegal" content based on complaints from aggrieved persons while sending directives to social media platforms under the new amendments.

What happens if your content is removed or blocked by the authority?

If your content is removed or blocked by the authority, you have the right to appeal to a tribunal. However, it’s important to note that the tribunal panel will be appointed by the federal government, raising concerns about its independence.

If you are a vlogger, social media user, or journalist, and you are dissatisfied with the tribunal’s decision, your only recourse is to appeal to the Supreme Court. Given the existing backlog and delays in case hearings at the Supreme Court, it is worth considering how long it might take for your case to be fixed or even admitted. This raises serious questions about access to justice and the fairness of the process.

Fighting these amendments feels like being in a never-ending round of Whac-A-Mole. Just as you address one issue around digital rights in this country, another one pops up. While we push back against this overreach, it’s essential to stay alert and know the risks.

Think twice before you post, share, or forward anything online and certainly not fake or false news, not out of fear but to ensure your voice isn’t stifled by these sweeping changes. In the meantime, let’s keep the pressure on to demand a digital space that’s fair, just, and free for everyone.

Nighat Dad is a lawyer, digital rights activist and founder of Digital Rights Foundation. She posts on X @nighatdad

Header and thumbnail illustration image by Geo.tv