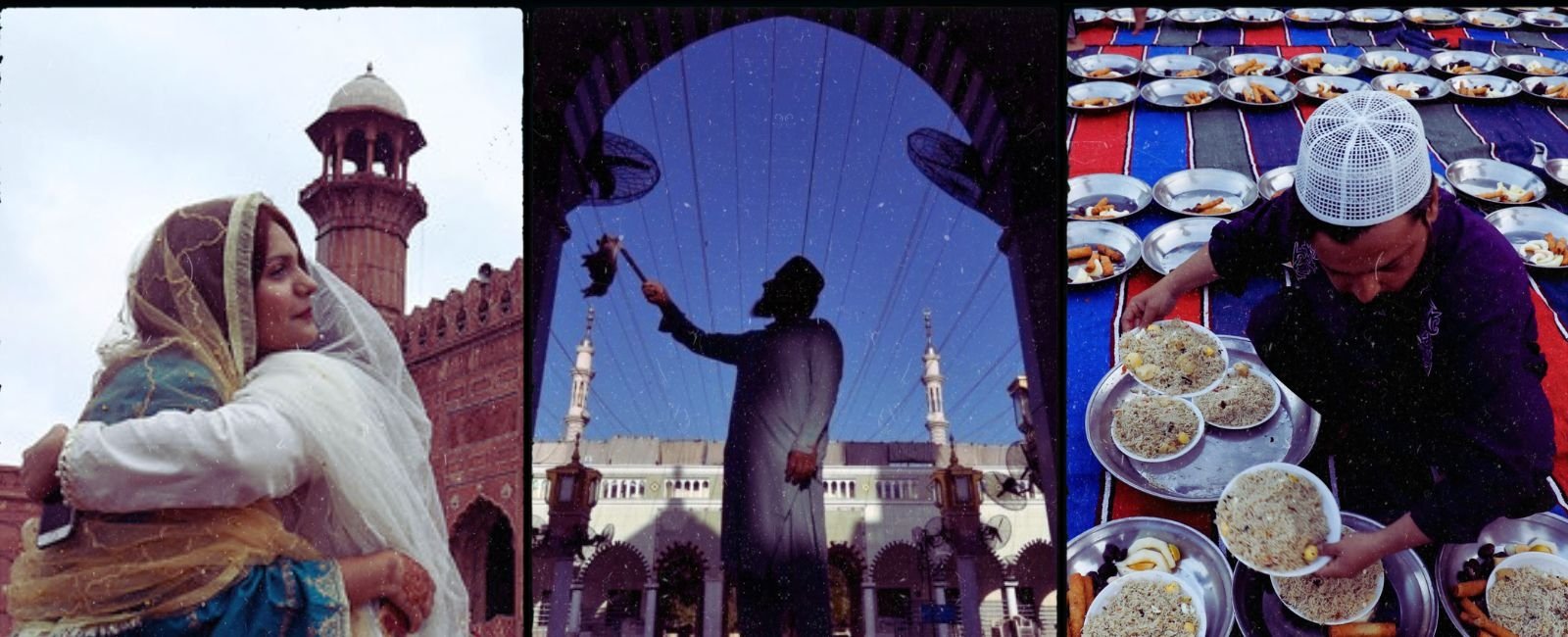

Beyond faith: Embracing Ramadan fasting for reflection and spirituality

Increasing number of non-Muslims observe fasting during holy month as an act of self-discipline, and cultural respect

"No one in my family knew I was fasting that day," says Raveena Kumari, a Hindu woman who grew up in Pakistan, as she shared her private observance of the Islamic tradition of roza (fast) to Geo.tv.

As Ramadan, the holiest month in the Islamic calendar, has commenced worldwide, including in Pakistan, Muslims have ardently embarked on a yearly sacred journey of fasting, devotion, cleansing, and self-discipline.

From dawn to dusk, they religiously refrain from all food and drink — even a single drop of water and also smoking — and from all acts prohibited by the teachings of Islam as they solemnise this spiritual time of worship and reflection. The fast begins with suhoor, the pre-dawn meal, and ends with iftar, the evening meal that marks the end of the fast.

Surprisingly, an increasing number of non-Muslims are observing Ramadan fasts, not as a religious obligation but as an act of solidarity and abstinence. It has somehow become an online trend with users on TikTok and YouTube documenting their experiences.

However, in Muslim-majority countries, non-Muslim fasting is not just an internet trend but also a sign of respect and cultural exchange.

Kumari, an MBBS graduate, reveals that growing up in a Muslim-majority country influenced her decision to fast in Ramadan.

“Honestly growing up with Muslim friends I know more about Islam than my own religion,” she quips, while speaking to Geo.tv. “I think this has somewhat influenced me to practise fasting during Ramadan.”

Psychologists suggest that our environment — including the people, culture, and surroundings — plays a crucial role in shaping our perceptions, values, and beliefs.

Clinical psychologist Shamyle Rizwan Khan describes that humans are wired for survival and social bonding.

“While these two primary order needs can come in contradiction with each other and can present the most challenging experiences of one’s life such as social pressure, systemic oppression and relational abuse — when the same needs are met, they elevate our healthy functioning and catalyse our performance in all life areas,” she adds.

Shamyle also highlights that humans naturally seek out "reference groups” that align with their values, explaining that “perception of who they are and where they belong” dictates our well-being.

For Raveena, her predominantly Muslim surroundings were a point of reference, and fasting became a familiar and significant experience outside of religious duty.

Recalling her experience, when she witnessed her first fast in 2018, she said that she kept it hidden, even from her family and friends from her community.

She owes one of her Muslim friends for showing her through Suhoor and Iftar, remembering him saying: "It's all about your neeyat (intent)."

For Kumari, fasting brought a sense of gratitude, peace, and calmness. She says, “Fasting brings peace, gratitude and harmony within me which is always a relief to my soul.”

Even on non-fasting days, she prefers to pay respect to her Muslim friends by not eating or drinking in front of them during the day, which speaks volumes about a sense of solidarity.

And this act of showing reverence is something which is practised by many non-Muslims during Ramadan.

Abana Sobel, a member of the Christian community, has a similar perspective. "Whenever I’m out with my Muslim co-workers or friends who are fasting, I never eat or drink in front of them out of respect," she tells Geo.tv.

She notes, “Although they never expect or ask me to do this, it's something I've been taught in my household.”

Abana also shares a cherished family tradition of hosting Iftar for Muslim friends and neighbours every Ramadan. "It's our way of showing support and respect. We make sure to cook something nice and send it to our neighbours for Iftar or host it at our house, even if we’re not fasting," she explains.

But Ramadan is more than a month of fasting. It is a period for introspection, heightened devotion, and refocusing one's faith through prayer, recitation of the holy Quran, and worship. Fasting is not merely abstaining from food and drink, but also purifying the soul, exercising patience, and fostering appreciation. During this month Muslims are also reminded to donate (give zakat) and be compassionate. It acts as a reminder of the struggles of the less fortunate.

Dr Ajay Kumar has been fasting during Ramadan for six years now. He reveals how the practice has helped him grow as a person.

Calling it a kind of annual detox, Ajay says, “I feel more in control of my life. While I am fasting, I know I have to control my anger, and my emotions, be more patient, and be kinder.”

“It’s also the time when I make sure to help those in need,” he adds. “I mean, we should help others and give to charity all year round, but during Ramadan, it feels even more meaningful.”

While Raveena kept her experience private to avoid scrutiny, Ajay on the other hand, had to face challenges for being open about it.

Despite some reactions, he remains unfazed, saying: “When it comes to religion, I have my own beliefs. I don’t let outside opinions affect me. It doesn’t matter.”

Ajay adds, “And fasting in Ramadan is all about my intent — it strengthens my connection with my own deities. I fast for the reward and out of respect for Islam.”

As highlighted by Shamyle "environments, including people and cultures, are powerful in shaping not only how we think and behave, but also our genetic structure encoding our strengths and vulnerabilities”.

Stories like those of Raveena and Dr Ajay go beyond just a personal choice. They reflect a growing sense of understanding that creates peace and harmony among communities.

Syeda Waniya is a staffer at Geo.tv

Header and thumbnail illustration by Geo.tv