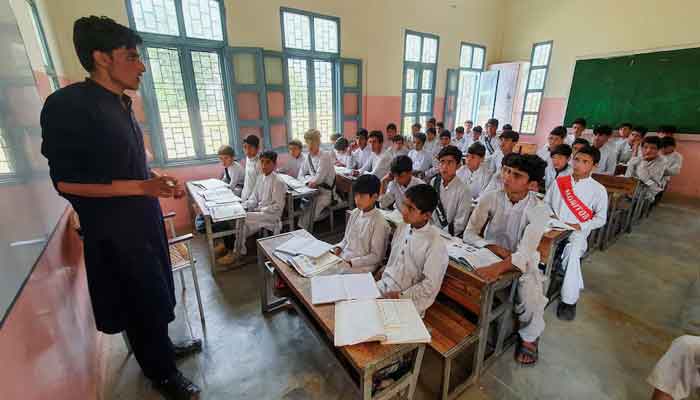

Education and development

Regardless of political systems democracy, autocracy, or monarchy no country has progressed without educating its people

March 03, 2025

About 60% of Pakistan’s population is functionally illiterate, as surveys count even those who can merely sign their name as literate. If computer and digital literacy were the benchmark, the actual illiteracy rate would be alarmingly higher, possibly 80%.

In today’s digital economy, computer literacy is essential for development. With industries increasingly reliant on automation, artificial intelligence, and data-driven decision-making, individuals without digital skills risk economic marginalisation. Countries that prioritise computer literacy gain a competitive edge in global markets.

Regardless of political systems — democracy, autocracy, or monarchy — no country has progressed without educating its people. Between 1909 and 1949, when the US economy doubled its gross output per hour of work, 88% of that increase was attributed to technological advances, according to Nobel Laureate Robert Solow.

Edward Denison estimated that between 1929 and 1982, around 52% of American economic growth came from advances in knowledge.

The Industrial Revolution (late 18th century) transformed economies and societies, driving the demand for a literate workforce. Britain, Germany, and the US introduced compulsory education in the 19th century, raising literacy rates beyond 90% by the early 20th century. The economic impact was astounding: Britain’s GDP doubled in 50 years (1750–1800) and grew fivefold in the 19th century.

Japan implemented the Gakusei education system in 1872 — under Emperor Meiji — achieving 80% literacy by 1900, fuelling rapid industrialisation.

In contrast, Latin American and African nations lagged due to political instability and colonial-era restrictions on education. By 1900, literacy in many African nations remained below 20%.

Public schooling expanded significantly in developed nations in the early 20th century, driving economic and technological advancements. By 1950, literacy rates in Western Europe exceeded 95%.

Post-World War II, global institutions like Unesco promoted literacy campaigns, particularly in newly independent nations. However, limited resources constrained developing countries’ progress.

In Asia, several countries undertook massive literacy programmes to modernise their economies. China’s literacy rate rose significantly due to government-driven campaigns under Mao Zedong’s leadership, reaching 66% by 1982.

Similarly, India’s National Literacy Mission, launched in 1988, sought to improve adult literacy, raising rates from 52% in 1991 to over 74% by 2011. The success of education systems in Japan and South Korea demonstrated how literacy could drive industrialisation, leading to rapid economic transformation.

Latin America pursued education reforms post-1950, with Argentina reaching 93% literacy by 1980 and Brazil 75%. Africa’s progress was uneven, with Egypt at 60% and South Africa over 80% by 1980. However, political instability hindered sustained reforms in many nations.

By the late 20th century, education became central to economic success. Developed nations expanded higher education, with universities driving research and innovation. IT and globalisation further underscored education’s importance in economic competitiveness.

Countries such as Japan (99% literacy by 1980), South Korea (98%), and Singapore (95%) rapidly modernised their education systems, achieving strong economic growth.

Meanwhile, India and parts of Southeast Asia struggled with educational disparities. South Korea and Taiwan’s democratic transitions were aided by rising literacy, whereas China and Vietnam maintained high literacy rates under authoritarian rule.

In Latin America, Argentina and Chile saw literacy improvements contribute to economic growth and democratisation. Brazil reached 90% literacy by 2010, but regional disparities remained. African progress was mixed — South Africa’s literacy surpassed 94% by 2020, while Nigeria and Kenya faced challenges, with literacy rates at 62% and 81% respectively.

The digital revolution has reshaped education, making learning more accessible through technology. Countries with high literacy rates, such as Finland (100%), South Korea (99%), and Germany (99%), continue to lead in innovation.

The democracy-education relationship remains complex. Some argue democracy promotes literacy through inclusive policies, while others believe education drives democratic participation. China and Vietnam demonstrate that high literacy can exist without political liberalisation.

Latin America faces challenges in using education for equitable economic growth. Mexico (95% literacy) and Brazil (93%) have expanded higher education, but inequality and corruption hinder progress. Argentina and Chile’s public university systems face funding and accessibility issues.

Africa’s educational landscape remains uneven. South Africa and Egypt (75% literacy) have developed university systems, but many Sub-Saharan nations struggle with access to quality education.

The Covid-19 pandemic further exposed digital learning disparities. However, global literacy rates have improved significantly due to efforts by governments and international organisations.

Education has been the cornerstone of economic and social progress for over two centuries. While industrialisation drove early literacy expansion, today’s knowledge economy requires lifelong learning. The relationship between democracy and education is complex, varying across regions.

As technology and globalisation reshape economies, education’s role in fostering innovation, equity and political engagement remains paramount.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

The writer is former head of Citigroup’s emerging markets investments and author of ‘The Gathering Storm’.

Originally published in The News