Pakistan's war within

On March 16, BLA claimed responsibility for Noshki attack on security forces, killing five officers and injuring dozens

March 27, 2025

The Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC) leader, Mahrang Baloch, was arrested by Quetta police last week while participating in a protest against police actions. The protest followed the arrests of several individuals, including BYC leaders, and conflicting reports about casualties.

The protest also involved relatives of missing persons demanding access to identify bodies brought to Quetta's Civil Hospital, with some reportedly taking corpses from the morgue.

On March 11, the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), a separatist group, carried out a brazen hijacking of a passenger train with around 440 passengers in Balochistan. The attack resulted in the deaths of 31 soldiers, staff and civilians.

On March 16, the BLA claimed responsibility for another attack on security forces in Noshki, killing at least five officers and injuring dozens. On March 17, Pakistan lodged a formal protest with Afghanistan over the alleged use of its soil in the train hijacking.

These recent attacks highlight the escalating threat of terrorism in a nation already grappling with decades of internal conflict. The hijacking is not an isolated event, but a stark reminder of the growing instability fuelled by failed policies, strategic miscalculations and an inability to implement meaningful reform.

A closed-door meeting of Pakistan's Parliamentary Committee on National Security (PCNS) resolved to tackle terrorist groups with an "iron hand" amid escalating terrorist incidents nationwide — particularly in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan.

The high-level session on March 18 was attended by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, Chief of Army Staff General Asim Munir, Director General of Inter-Services Intelligence Lieutenant General Asim Malik, the chief ministers of all four provinces, and other top officials.

Former prime minister Imran Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) boycotted the meeting in protest against the government's refusal to let its leaders meet the incarcerated party founder or allow him to attend the meeting.

COAS Gen Asim Munir pointed to governance gaps as a major reason behind the spike in terrorism and called for making Pakistan a "hard state".

The communique issued after the PCNS meeting did not mention the role of the Afghan Taliban in sheltering the TTP on Afghanistan soil. The statement issued by the PCNS read like many in the past decades or so, noting the "need for a national consensus to repel terrorism, [and] emphasising a strategic and unified political commitment to confront this menace with the full might of the state".

Pakistan is once again at a crossroads, besieged by a resurgent wave of terrorism that threatens to unravel the fragile fabric of the state. This crisis is no sudden calamity; it is the cumulative result of years of mismanagement and a series of decisions that have repeatedly steered the nation towards self-destruction.

In October 2024, Maulana Fazlur Rehman said that the government had lost the writ in KP and Balochistan because of the widespread lawlessness, which made people's lives and properties unsafe there.

Rehman recently warned that "Pakistan's physical boundaries might be altered sooner rather than later" — unless drastic measures were taken to address pressing concerns, including the lack of state writ in the provinces of Balochistan and KP as well as the newly-merged tribal districts.

The evolution of terrorism in Pakistan tells a grim story. In the early 2000s, as Al-Qaeda and its affiliates carved out safe havens in its northern tribal areas, Pakistan was already grappling with the seeds of its internal strife. By the mid-2010s, the rise of the TTP escalated violence into an all-out internal conflict.

Military operations temporarily reduced the bloodshed — dropping annual attacks from a staggering 2,000 in 2009 to fewer than 400 by 2019. However, the 2021 Taliban victory in Afghanistan fanned these embers into a raging inferno.

According to the Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies, Pakistan experienced a total of 521 terrorist attacks in 2024, marking a 70% increase from the previous year.

This intensified wave of terrorism claimed 852 lives, reflecting a 23% rise compared to the terrorism-related fatalities recorded the year before. Another 1,092 people were injured in these attacks recorded during the year.

The crisis in Pakistan is as much about internal mismanagement as it is about external forces. During the past five years, the misguided policies of the Imran Khan administration turned what could have been a calculated counterbalance against India into a strategic debacle.

By regarding the Afghan Taliban as potential allies against India, Islamabad inadvertently provided sanctuary to the very elements that now imperil its security. This embrace of extremist proxies has backfired monumentally. Militant groups initially seen as strategic assets have evolved into destabilising forces that fuel a cycle of violence and radicalisation.

Pakistan's stability is critical for regional security. It shares borders with Afghanistan, China, India and Iran — nations with overlapping strategic interests and historical tensions. Its role as a nuclear-armed state further amplifies its importance.

A long-simmering insurgency continues to grip Balochistan, a region plagued by neglect, systemic repression and economic exploitation. Since Pakistan's independence in 1947, the state has launched at least five major military operations in the province — in 1948, 1958, 1967-68, 1973-77, and from 2006 to the present.

The conflict escalated in 2006 when Pakistani forces clashed with militants, resulting in the death of prominent leader Nawab Akbar Bugti, fuelling further unrest.

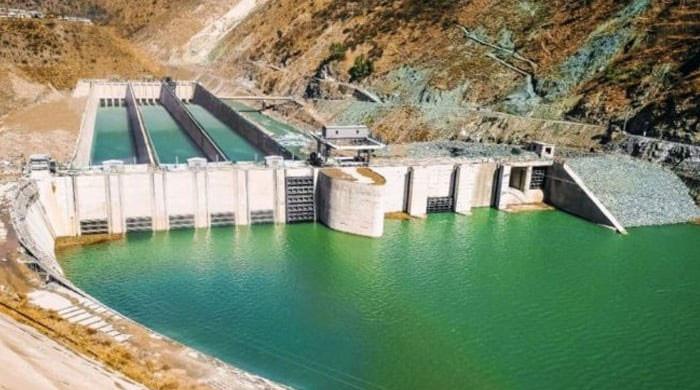

Militant groups repeatedly target Chinese workers and infrastructure. The attacks targeting CPEC projects, which include the development of the strategic seaport of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea, highlight how domestic instability undermines Pakistan's strategic partnerships.

This dynamic also reveals a deeper truth: without addressing the socio-economic grievances that have festered over generations, any attempt at counterterrorism remains superficial.

Pakistan's strained relations with India and Afghanistan exacerbate its security challenges. These dynamics not only threaten to destabilise South Asia but also risk dragging global powers into regional conflicts.

Islamabad's repeated claims that India’s RAW has been supporting the insurgents in Balochistan and elsewhere serve as a stark reminder of the deep-rooted regional animosity that underpins these crises.

While New Delhi steadfastly denies these allegations, mutual suspicions have deepened over the years. The 2019 Pulwama attack, which nearly ignited a full-scale nuclear confrontation, is emblematic of how terrorist proxies have become pawns in a larger strategic game that endangers all regional stakeholders.

Then, there is a growing military relationship between Pakistan and Bangladesh, which has raised eyebrows in Delhi. A high-level Bangladeshi military delegation made a rare visit to Pakistan in January and held talks with the COAS.

In February, the Bangladeshi navy also participated in a multinational maritime exercise organised by Pakistan off the Karachi coast.

Pakistan's internal crises are rooted in governance failures, economic stagnation, and social fragmentation. Chronic corruption and political instability have stifled economic growth, leaving millions impoverished. This economic despair fuels radicalisation and weakens state institutions. The civilian leadership stands sidelined, undermining democratic accountability.

Provinces like Balochistan suffer from systemic neglect and repression. The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances, convened by the government, recorded 2,752 active cases of enforced disappearances in the province as of January 2024.

Heavy-handed military responses have only deepened grievances, making counterinsurgency efforts ineffective. Decades of using extremist groups as strategic assets have backfired, creating a cycle of violence that now threatens the state itself.

Although law enforcement and intelligence agencies must actively pursue terrorists, a strategy that relies solely on counterterrorism measures is doomed to fail. To stabilise Pakistan and secure its geopolitical relevance, Pakistan must decisively end its reliance on militant groups for strategic purposes.

This requires a reorientation of foreign policy towards peaceful coexistence with neighbours. The country must initiate constructive engagement with India, Afghanistan and Iran to reduce tensions and mutual distrust.

The Baloch insurgency of the 1970s serves as a stark reminder that local conflicts often become battlegrounds for international power struggles. In 1976, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto sought to resolve bilateral issues by reaching out to then-Afghan president Mohammed Daoud. During Bhutto's visit to Kabul in June of that year, both leaders agreed to cease hostile propaganda, particularly targeting ethnic minorities in their respective countries.

This visit was followed by Daoud's visit to Pakistan in August 1976. In June 1977, Bhutto stopped in Kabul while returning from Tehran to meet with Daoud, further solidifying their rapport and discussing ongoing issues.

These exchanges marked a significant period of cooperation and dialogue between Afghanistan and Pakistan, with both sides showing willingness to resolve long-standing disputes. However, this progress was halted by the communist coup in Afghanistan in April 1978 and Bhutto's ouster in July 1977.

Pakistan's future hangs in the balance. Its choices will determine whether it remains trapped in cycles of violence or emerges as a stable country. Given its geopolitical significance, Pakistan's stability is not just a national imperative but a global necessity.

The writer is the former head of Citigroup's emerging markets investments and the author of 'The Gathering Storm'.

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer's own and don't necessarily reflect Geo.tv's editorial policy.

Originally published in The News