Will EVs help clean Pakistan's air — or just shift pollution elsewhere?

A national EV policy is a key step, but its impact hinges on aligning with broader energy, transport, and industrial reforms

In November 2024, three-year-old Amal Sukhera, represented by her mother and legal counsel, filed a petition in the Lahore High Court. The case accused the Punjab government of failing to protect citizens from worsening air pollution — a violation, they argued, of the constitutional right to a clean and healthy environment.

The case coincided with one of Pakistan’s most sustained periods of toxic smog — and, some say, marked a turning point. Organisations such as Lahore Bachao Tehreek and Lahore Conservation Society coordinated protests against the lack of government initiative towards solving the smog crisis.

It also marked a shift in political momentum. Within months, the government had revived its dormant electric vehicle (EV) plans. New policy drafts were circulated, foreign automakers made inroads, and the first fast-charging EV station was unveiled in Lahore.

Climate advocates have hailed the renewed push as a forward-looking strategy — but questions remain over whether it reflects a serious commitment to long-term transition or simply a reactive move in the face of growing public pressure.

A turning point – but is it the right path?

The outrage resulted in Pakistan’s first National Electric Vehicle Policy (NEVP), approved in 2019 under former minister for climate change Malik Amin Aslam. The policy promised an enterprising overhaul of the system. However several climate activists, researchers, and lawyers widely criticised it for being overly ambitious, difficult to implement, and detached from the country’s infrastructural and political realities.

”The desire to perform an efficient energy transition was suddenly made a primary concern by the Punjab government, the federal government as well as the power ministries, it was a huge push,” says Yasir Darya, founder of Climate Action Center (CAC), who played a crucial role in the advocacy of this policy.

He says while the previous policy didn’t hit the mark, the push towards EVs saw a revival after the last spell of smog.

This past winter, Lahore recorded some of its worst-ever Air Quality Index (AQI) levels, with readings frequently soaring above 400, placing it in the “hazardous” category and making it briefly the most polluted city in the world. The city was cloaked in a thick, chemical-tinted fog, reducing visibility and leaving residents with burning throats, itchy eyes, and persistent coughs.

For Pakistan, smog isn’t the only challenge. Annual floods, heatwaves, and droughts have been getting increasingly worse in the last few years. The 2022 floods left one-third of the country underwater and killed 1,700 people.

For a country that contributes little to global emissions yet suffers some of the worst climate impacts, the shift to EVs is about more than just transportation. Pakistan's transport sector was responsible for 43.3 million tonnes of planet warming carbon dioxide emissions, representing 22% of the country's total emissions, according to a 2023 report by the Asian Transport Observatory indicates. Another study found that road transport alone accounts for around 23% of Pakistan's total greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet, despite the climate urgency, environmental issues rarely dominate domestic politics. Even though climate struggles to become a priority in national discourse, it has definitely climbed up the ranks.

While policy momentum has returned, questions remain about whether the efforts are heading in the right direction. While reducing transport emissions could help Pakistan with both the air pollution and climate targets, there are concerns about whether the infrastructure is ready, whether the policies are realistic, and whether this transition will benefit those who need it most.

Policy promises – and past failures

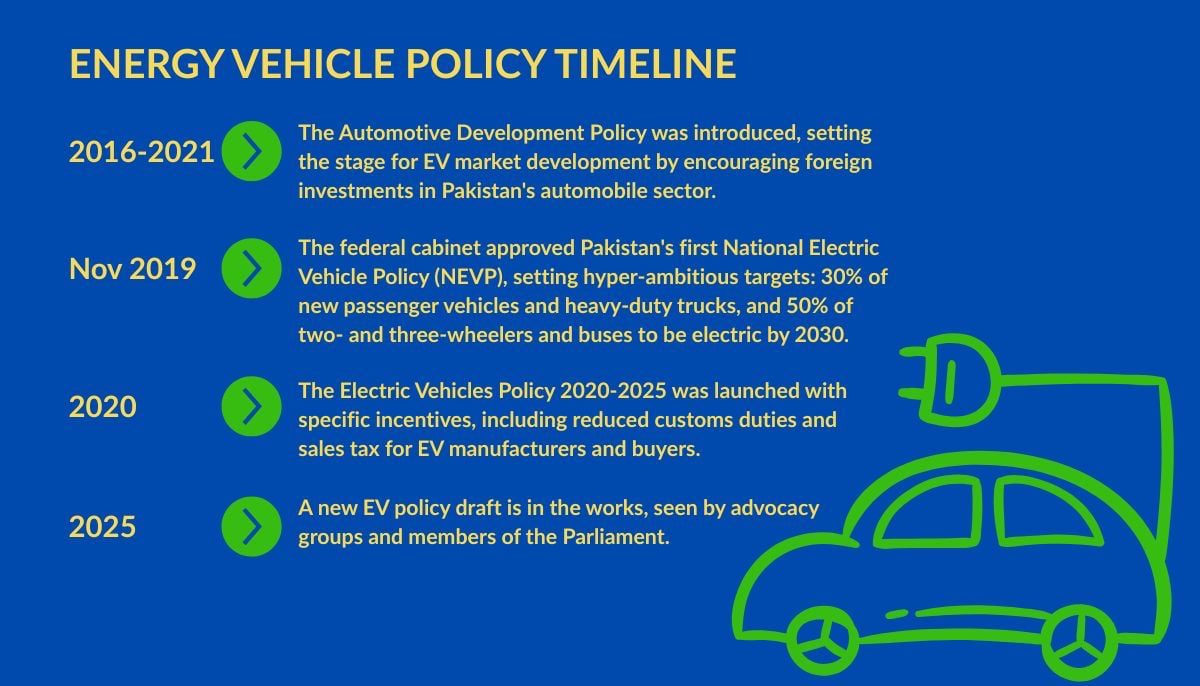

Pakistan's electric vehicle strategy has evolved significantly over the past decade:

- 2016-2021: The Automotive Development Policy was introduced, setting the stage for EV market development by encouraging foreign investments in Pakistan's automobile sector.

- November 2019: The federal cabinet approved Pakistan's first National Electric Vehicle Policy (NEVP), setting hyper-ambitious targets: 30% of new passenger vehicles and heavy-duty trucks, and 50% of two- and three-wheelers and buses to be electric by 2030.

- 2020: The Electric Vehicles Policy 2020-2025 was launched with specific incentives, including reduced customs duties and sales tax for EV manufacturers and buyers.

- 2025: A new EV policy draft is in the works, seen by advocacy groups and members of the Parliament.

EVs make up just 0.16% of Pakistan’s auto market. According to a recent study of 511 consumers, awareness and incentives remain key gaps. However, as Pakistan struggles with the high costs of petrol and diesel, consumers are increasingly beginning to see EVs as a viable option.

“The biggest benefit is that it charges within three hours and allows me to drive it for almost a hundred kilometers, which is quite some distance, if you think about it,” said Falak, 22, a resident of Islamabad who switched to an electric bike.

The first quarter of 2025 has brought an unusual flurry of activity. On February 4, the government licensed 55 new EV manufacturers. Days later, Chawla Group launched Chinese-made Dongfeng EVs in Pakistan.

Chinese EV giant BYD shipped its first commercial consignment to Karachi Port on February 12. That same month, Pakistan and China signed strategic cooperation agreements for EV development and infrastructure, including a plan to co-develop a “national car.”

Federal Power Minister Awais Leghari inaugurated Pakistan’s first 120 kW fast-charging EV station on March 25. But experts say the road to a sustainable transition remains long.

Senator Sherry Rehman, chair of the Senate Standing Committee on Climate Change, highlighted in January 2025 that the country produced only 60,000 EVs against a target of 600,000.

Does the new policy have answers?

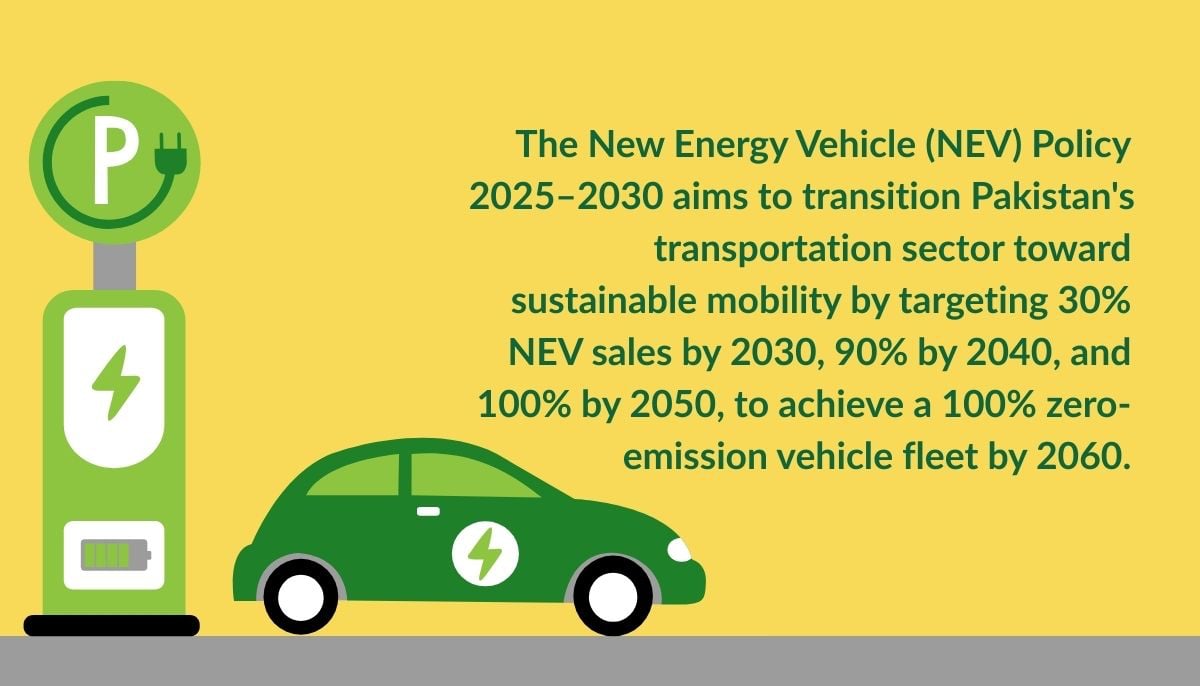

A new policy framework — the New Energy Vehicle (NEV) Policy 2025–2030 — has been quietly circulating among parliamentarians and climate advocates. The draft, titled “v27 Internal Draft Policy Document” shows a significant step up from the earlier version.

The new policy includes expanding the scope to include battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), and fuel cell EVs (FCEVs). It also proposes detailed incentives for local manufacturing, including customs duty exemptions and tax breaks on components like batteries, motors, and electronics.

The NEV 2025 aims to transition Pakistan's transportation sector toward sustainable mobility by targeting 30% NEV sales by 2030, 90% by 2040, and 100% by 2050, to achieve a 100% zero-emission vehicle fleet by 2060.

A request has been sent to the climate ministry to confirm the details of the draft.

What the new policy includes:

- Clear tax and tariff exemptions for EV components.

- National targets for charging infrastructure rollout.

- Battery recycling guidelines.

- Workforce training programmes and a National EV Fund.

- Plans to utilise excess electricity capacity while decreasing oil imports.

The NEV 2025 aims to transition Pakistan's transportation sector toward sustainable mobility by targeting 30% NEV sales by 2030, 90% by 2040, and 100% by 2050, with a goal of achieving a 100% zero-emission vehicle fleet by 2060.

Despite economic volatility and political uncertainty, electric bike sales grew in 2024 and are expected to rise. Darya says the trend is being driven not by climate awareness, but by necessity.

“Owing to the spreading poor air quality, 100% NEV motorbikes, including electric, retrofitted and hybrid, will gradually replace gasoline motorcycles to ensure a pollution-free environment, reduce health hazards and provide a cheaper source of transportation.”

The policy’s broader goals include reducing oil imports, using surplus electricity, and strengthening local manufacturing. Most importantly, it charts a pathway for phasing out oil dependency — while targeting carbon reductions over the next decade.

Still, the shift comes with fiscal trade-offs. A November 2024 report estimated that Pakistan could lose up to $5.68 billion in fuel tax revenue due to EV adoption.

“I think sometimes in an elected government the state has to deal with multiple stakeholders before ensuring successful implementation of a policy; however, in this hybrid regime the state is able to pressurise the IPPs to modify agreements, so in EVs also we are seeing a very strong push,” said Darya.

The NEV policy includes timelines for national charging infrastructure, electricity pricing reforms, and consumer incentives. It outlines the creation of an Energy Vehicle Support Fund, a Center of Excellence, provincial coordination plans, and battery recycling protocols.

“This new policy targets the phasing out of petrol-consuming vehicles until 2060. So by 2050, no car should be sold that runs on petrol. This phasing out of petrol cars is why we are supporting it, and the style of government is conducive to getting this done fast and efficiently. It’s happening,” Darya stated.

The new policy draft mentions public transport primarily in Section 9.5 "Public transport through public-private partnership," where it states that "public transport will be encouraged to shift on NEVs" and that "intra-city transport will be converted into NEVs with the partnership of public and private sectors."

The policy also mentions incentivising ride-hailing companies to deploy NEV pilot projects in provincial capital cities, and offering 0% interest loans for commercial NEV use. However, these provisions are relatively brief compared to the detailed incentives for personal vehicle electrification and manufacturing.

In February 2025, Punjab Chief Minister Maryam Nawaz launched a pilot project introducing 27 electric buses operating from Lahore Railway Station to Green Town.

The Punjab government approved a plan in April 2025 to deploy 1,500 electric buses across multiple cities, with the first phase introducing 380 buses in Lahore and Gujranwala.

The Sindh government approved a four-year plan in January 2025 to add 8,000 electric buses to Karachi's public transport system, aiming to modernise commuting and reduce air pollution.

“When we look at developing countries like Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh, we must understand the geopolitical influences that shape inequality,” says Harjeet Singh, Global Engagement Director at the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative.

“BYD might not be interested in public transport — and few people in the country can afford their vehicles — but you have to start somewhere.”

Local assembling is also picking up pace. Dewan Farooq Motors assembled over 100 Chinese EVs in just three months. Atlas Honda — with 85% of Pakistan’s two-wheeler market — has announced its first electric bike for June 2025. But many startups remain reliant on imported components like motors and battery cells.

Darya believes that Pakistan’s labour market may also play a role.

“China is looking for cheap labour — this is an opportunity for Chinese companies to find that, and in doing so, they’ll transfer skills to the native population.”

Is Pakistan’s EV shift truly sustainable?

The environmental benefits of electric vehicles depend heavily on the source of electricity used to charge them. Currently, a significant portion of Pakistan's electricity still comes from fossil fuels, particularly coal and natural gas.

Without a parallel shift toward clean energy, experts warn, the country risks swapping one polluting system for another.

“The environmental benefits of EVs are only meaningful if the grid itself becomes cleaner,” says Harjeet Singh, climate activist and founding director of Satat Sampada Climate Foundation.

The challenge, however, is not unique to Pakistan. Countries across the Global South face similar tensions between economic constraints and the need for a just energy transition.

Ebipere Clark, special adviser on infrastructure to Nigeria’s Central Bank, says Pakistan should look toward countries that have used bold policy levers to reshape energy use.

“Ethiopia is the best country for EV transition because of its abundant hydropower potential,” he says

“They have a 100% tariff on internal combustion vehicles — they didn’t have an EV infrastructure, but the tariff forced one into existence.”

Pakistan’s case, however, is more complex. Without abundant hydropower or clean baseload capacity, charging an EV could still mean burning coal, with little real reduction in emissions. The so-called “well-to-wheel” impact may end up being closer to conventional cars than advocates would like to admit.

“Fossil fuel sources are still being controlled by big industrial families, and the same families are now getting into green power. Industrialisation has been slow in Pakistan, and with the debt, there is urgency. State policy must reflect long-term perspectives,” Singh says.

None of this means the EV transition is pointless — but it does mean the gains will be limited unless they are part of a broader shift.

The country’s EV policy is an important step toward lowering emissions and cutting urban air pollution. But its success will depend on how deeply it integrates with Pakistan’s overall energy strategy — including renewables, public transport, and long-term industrial reform.

As the country navigates this transition, experts say, policymakers must keep the bigger picture in mind: a cleaner vehicle fleet will only go so far if the electricity behind it remains dirty.

Areeba Fatima is an investigative journalist, fact-checker and researcher based in Karachi.

Header and thumbnail illustration via Canva