Fleeing terror, finding fear

KARACHI: Jalal, 40, moved from his native Bajaur Agency to Karachi nearly 25 years ago in search of better economic prospects. It was stressful, but he has made a steady living selling roasted...

October 11, 2014

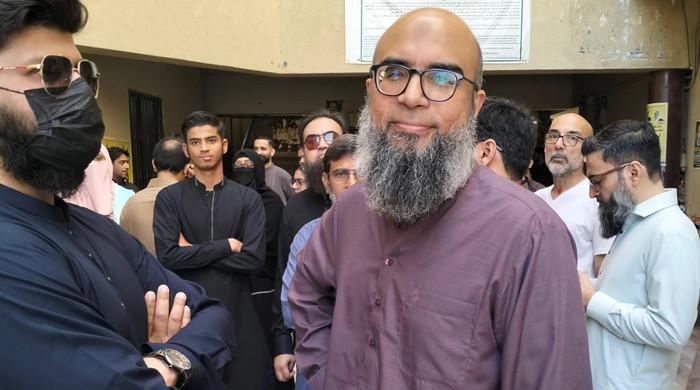

KARACHI: Jalal, 40, moved from his native Bajaur Agency to Karachi nearly 25 years ago in search of better economic prospects. It was stressful, but he has made a steady living selling roasted corn from a street cart.

In his many years in the metropolis, it was rare for Jalal to see people come here from his hometown. But now, because of the violence and the ensuing counterinsurgency operation in the mountainous region, unemployed and unskilled men are leaving in large numbers and coming to Karachi. It has created new stress for Jalal.

“We were just four to five persons living in this 10×20 room…. But now there are 10 people in the same place and in inhumane conditions,” Jalal said while sitting in courtyard of his one-room home in the early morning as he prepared his goods for the day.

For villagers, the local economy is mostly pastoral. The tribesmen lack skills, so when they migrate to bigger cities they face bigger challenges to survive and support their families back home.

Terrorism in Pakistan has not just inflicted pain, misery and monumental losses to property, it has inflicted long-term damage to the socio-economic fabric of the tribesmen from a region that was once a stronghold for the militants.

“Whenever an act of violence took place in our hometown or here in Karachi we all got worried,” said Jalal. “We have no means to communicate with them and check whether they are fine or not, neither they can talk to us in case there’s an emergency, so we leave everything on the mercy of Allah.” He says he and other villagers have to send a message to their families two days prior to set up a time to talk. Because the mobile signals are weak in the village, their family members have to walk to a higher place where the connection is stronger.

Mahnoor, another resident of Jalal’s village, fled war-torn Bajaur nearly eight years ago. He says life in the city is painful. “I am the sole bread earner of my family comprising eight dependents,” Mahnoor told us, while working on a hot September afternoon. He and others make money selling roasted corn on the streets from pushcarts outfitted with wood-fired stoves. “One can’t sit on fire,” he said, “but we are making our livelihood working with fire all day long.”

And though they escaped the violence in their region, they face ethnic violence and anti-Pashtun sentiment in the city. “They (political activists) come to us and threaten us,” Mahnoor said, “but we are helpless we can’t defend ourselves in these circumstances and can’t go back home either.”

“While we work all day long from dawn to dusk, the cops make our lives more miserable,” said Jalal. “We earn 350-400 rupees a day and have to pay them Rs 50/day as extortion.” He also explained that the exploitation does not end with the payments. Jalal says law enforcement regularly searches the area just to get easy arrests, since they know the tribesmen often don’t have proper documents.

Government figures put the population of Fata (Federally Administered Tribal Areas) regions at around 3 million. But others say the figure is higher, closer to 4.45 million. A military operation in tribal belt forced the residents to flee and took refuge in other parts of the country. There is no official word as to how many IDPs came to Karachi.

Estimates show that Pashtun population in the city has grown exponentially during the past several years and now nearly five million of them are living in the city. That gives a new twist to the violence in the metropolis.

Police believe that they have concrete evidence that terrorists in the city have moved here under the guise of refugees from northern areas. SSP CID Raja Umar Khattab, who is heading counterterrorism cell of Karachi Police, said there are linkages between the IDPs and the violence in the city. “The tribesmen fleeing military operation are not hardcore militants they are the facilitators mostly, but at times such help becomes crucial.”

The misery does not end here for the fled Pashtuns. Jalal and others will walk with their carts some 8kms each day from dawn to dusk. And if anyone of them falls sick it can be a problem for the whole group.

Even as the number of displaced people in the metropolis grows, the government and local administrations do not seem alarmed. But the situation can have a haunting impact on the economy and security, when poverty compels these tribesmen to opt for a more criminal means of making a living.

Shot with a mobile device, this multimedia story was produced by Wasif Shakil/Adnan Rashid/Shah Nawaz in partnership with the Center for Excellence in Journalism (CEJ) at the Institute of Business Administration (IBA) in Karachi.